|

This website is a complete book and

will load slower for dial-up users.

Please be patient for pictures.

This website is dedicated to the brave and

dutiful Ontarian,

Patrolman Henry Raymond Craig

Henry's family sent me his picture

when they discovered this website.

"Mr. Thompson probably owes

his life to the fact that he ran to the south

gate to give the alarm when the first outbreak of fire was noticed.

He said that while he rushed to the gate, Craig ran down the jetty

towards the fire."

Henry was/is remembered fondly by his large family as a

very loving young man.

He grew up on a farm in Aberfeldy, Ontario and was one of twelve children.

HALIFAX BLAST KILLED ABERFELDY SOLDIER

Click here to read about Henry on Genealogy.com

And here is a newspaper clipping and memorial with his picture at

Veterans Affairs Canada

Awards

to the Royal Canadian Navy

http://www.rcnvr.com/C%20-%20RCN%20-%20WWII.php

CRAIG, Henry Raymond,

Patrolman (Posthumous) (V-63822) - Mention in Despatches -

RCNVR - Awarded as per Canada Gazette of 5 January 1946. Home:

Harrow, Ontario.

CRAIG. Henry Raymond, V-63822, Patrol, RCNVR, MID~[5.1.46]

"For outstanding valour in the face of fire during the Magazine

explosion at Halifax in July, 1945. this rating was on duty at

the south jetty when the first explosion occurred. He turned in

the necessary alarm and then attempted to proceed to the scene

to help extinguish the fire. He was killed by the ensuing

explosion before he could reach the scene. His bravery and

resource were in keeping with the highest traditions of the

Canadian Naval Service."

---------

Also remembered is B. J. Pothier

who was

lost at sea in 1947

dumping explosion ammunition, a practice we have long come to

regret.

Note from the Publisher:

This website book is based on a previous

website I published years ago about a

letter written right after the explosion by a man named Cyril in Halifax to his

mother in Cape Breton.

The newspaper article on this other webpage is about this author and

the compiling of this book.

You can read the previous website by clicking this link.

The Other Halifax Explosion July 18-20, 1945

A Letter from Cyril

For Nova Scotians

and those who know not the details of this event, prepare yourself for the

riveting tales

of your local history and the absolutely fantastic

stories of civil service and duty by great

men, women, neighbouring towns and much more that transpired 68 years

ago, before, during and after...

The Other Halifax Explosion!

THANK YOU!

To

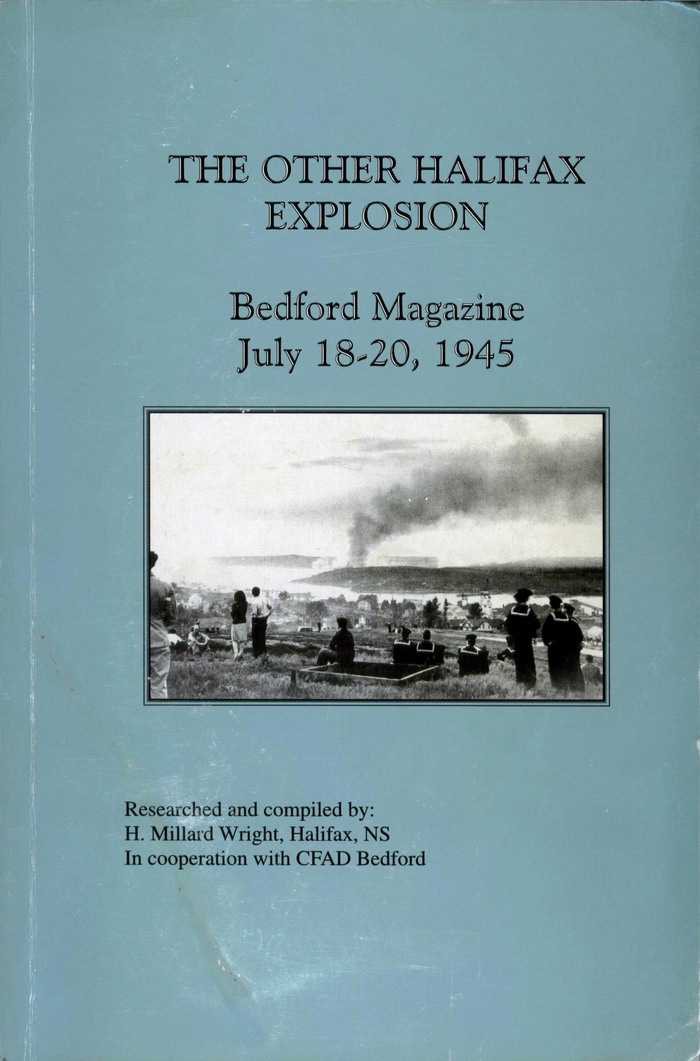

H. Millard Wright

For "researching and

compiling"

"He retired in 1992 and began writing as a hobby."

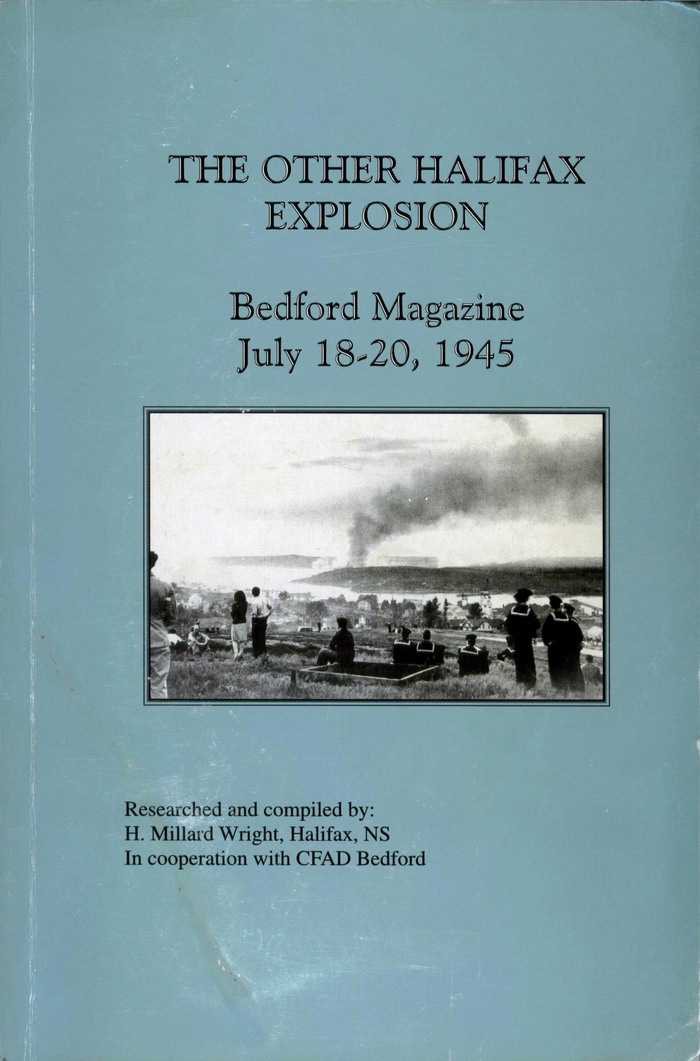

THE OTHER

HALIFAX EXPLOSION

Bedford Magazine

July 18-20, 1945

INDEX

The chapters are all linked for jumping

down and book marking.

Be sure to scroll through, as all the many pictures are not linked.

Introduction

Chapter l,

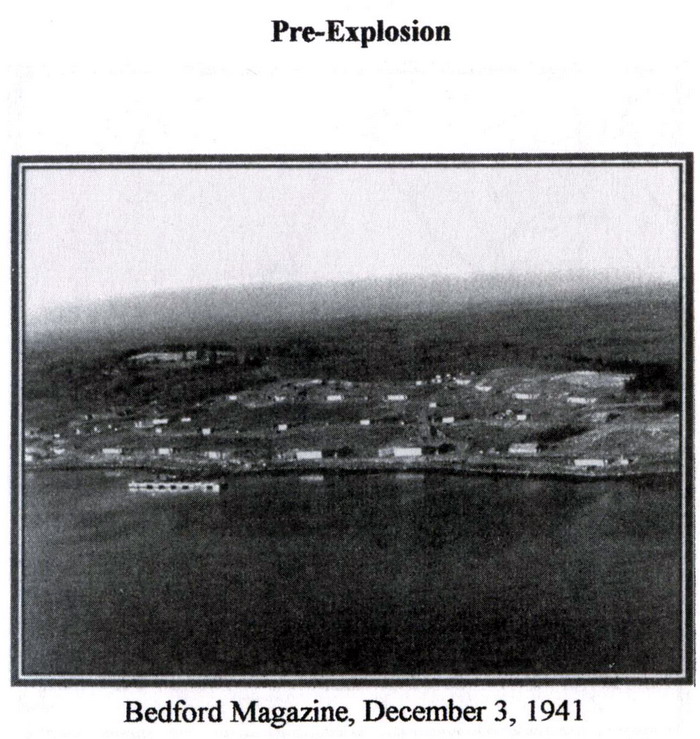

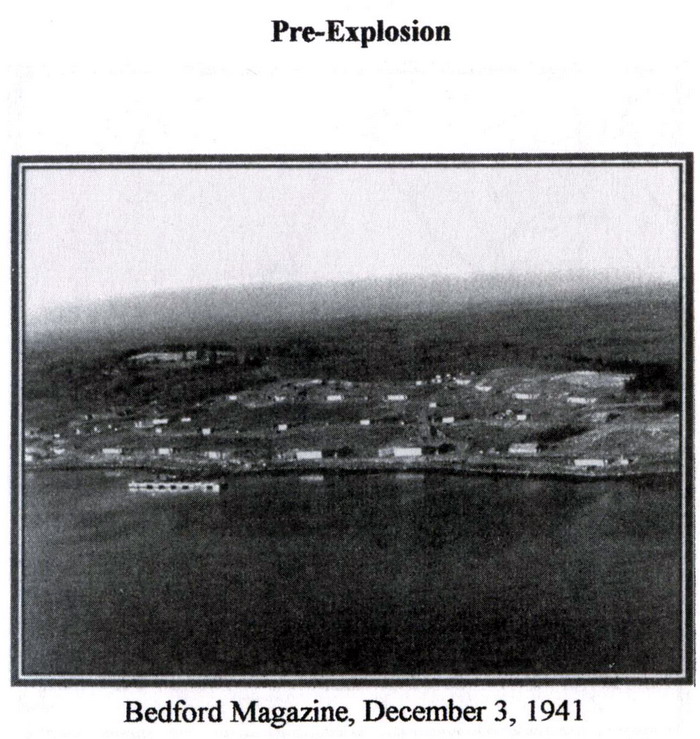

Pre-Explosion

Chapter 2,

July 18, Explosion and Evacuation

Evacuation

Emergency Services

Chapter 3,

July 19, Explosions Continue

Chapter 4,

July 20, Returning Home, Recollections

Recollections

Chapter 5,

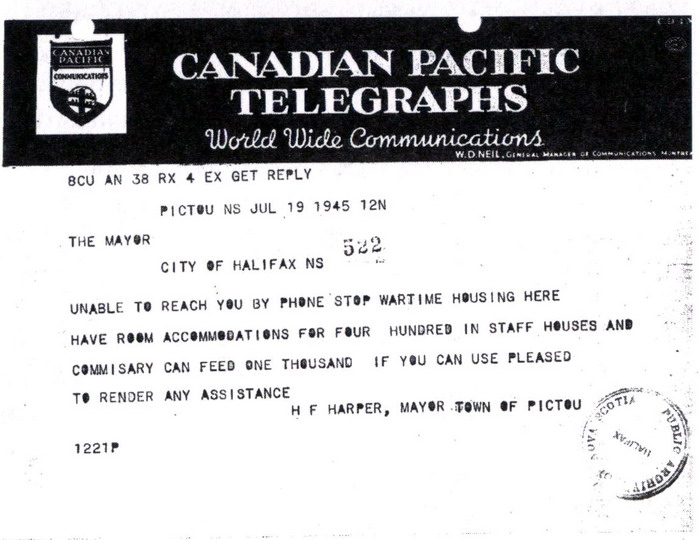

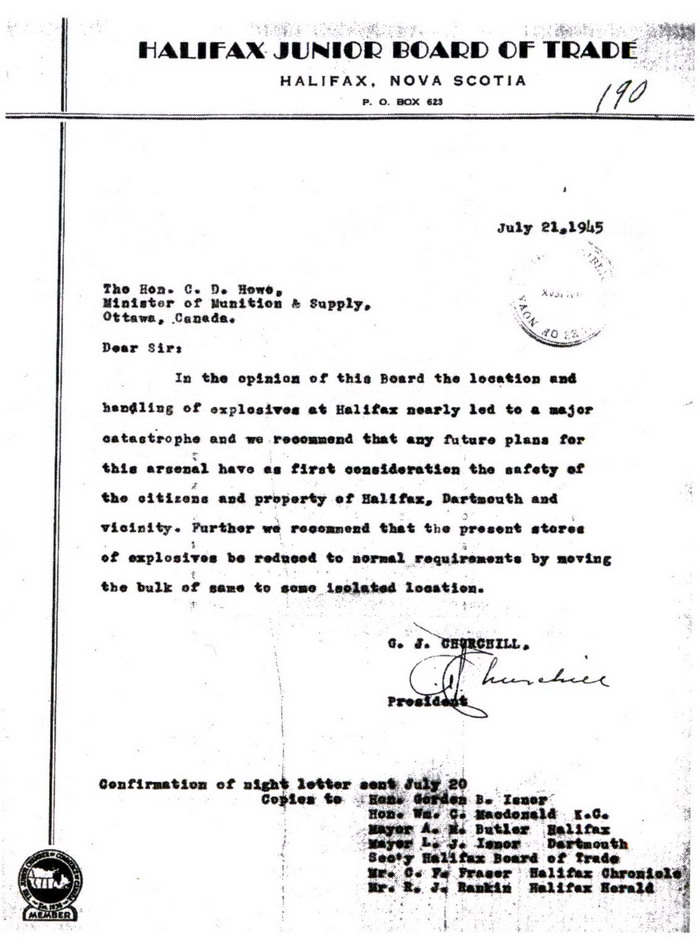

Outside Help, Correspondence

Chapter 6,

Aftermath

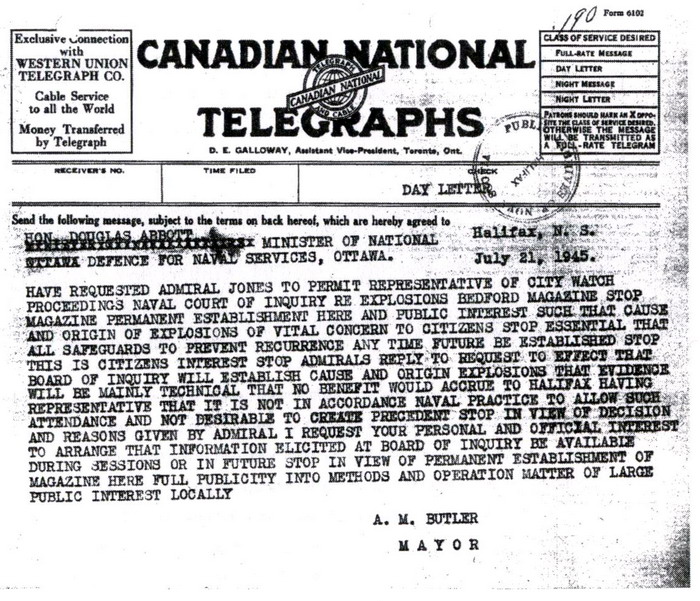

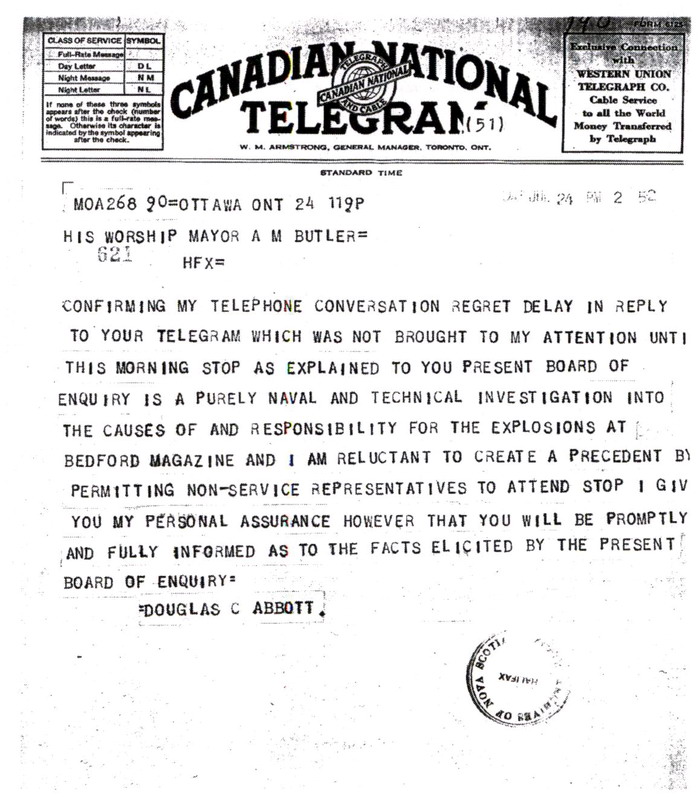

Chapter 7, The

Inquiry

Chapter 8,

The Minister’s Press Release

Chapter 9, The Story

From Inside

Chapter l0,

Epilogue

Special Acknowledgements

Resources

& The Author

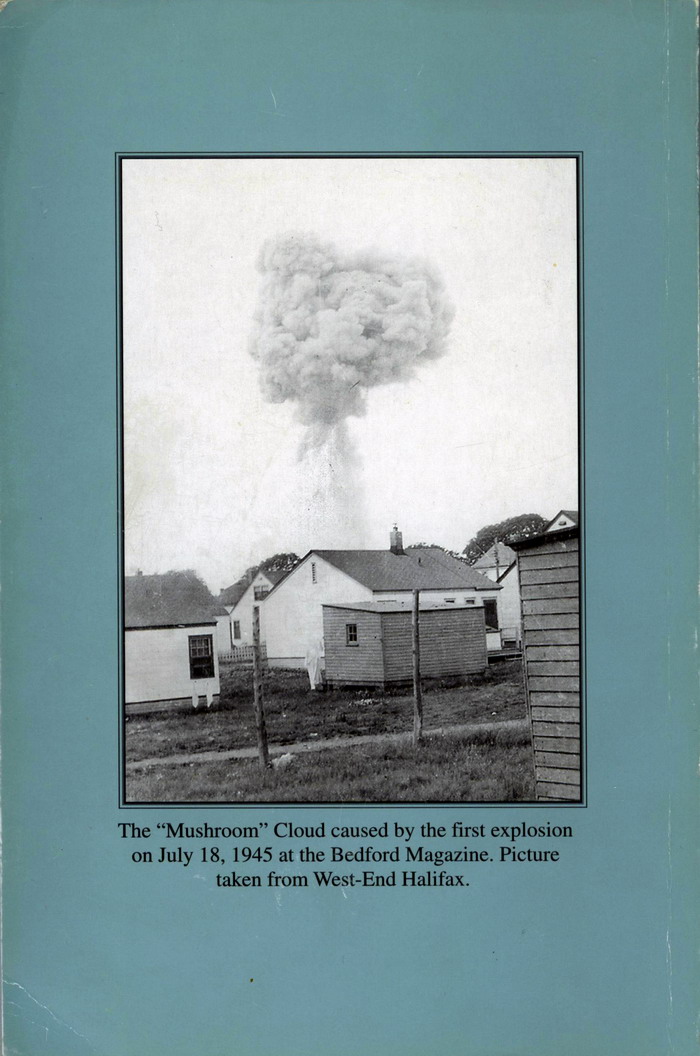

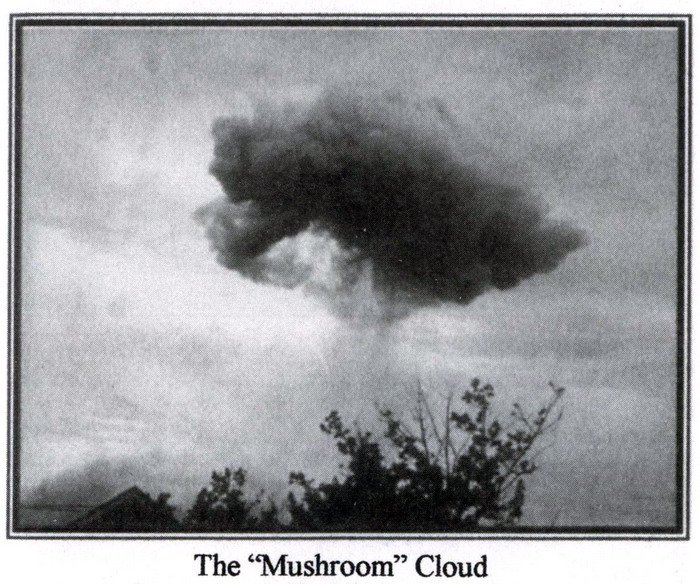

Back Cover with Mushroom Cloud

Introduction

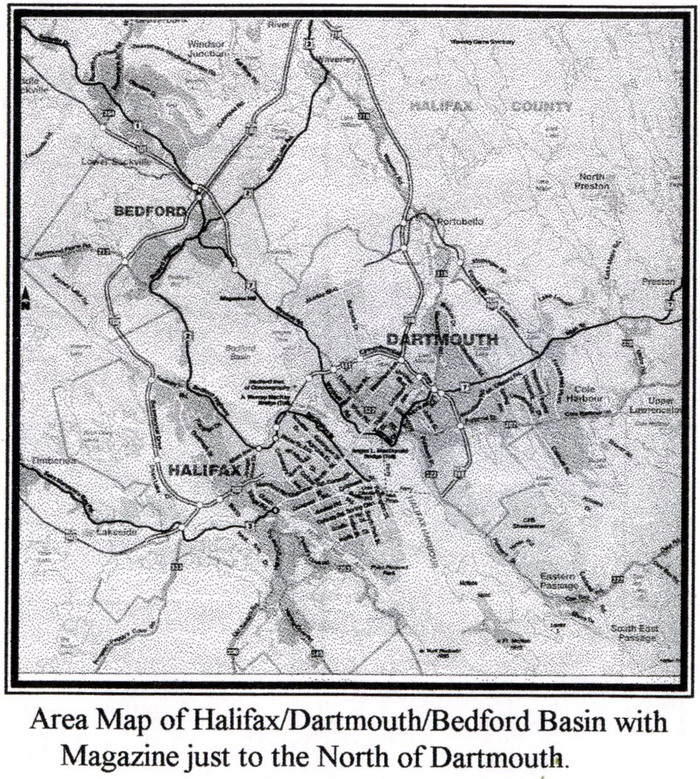

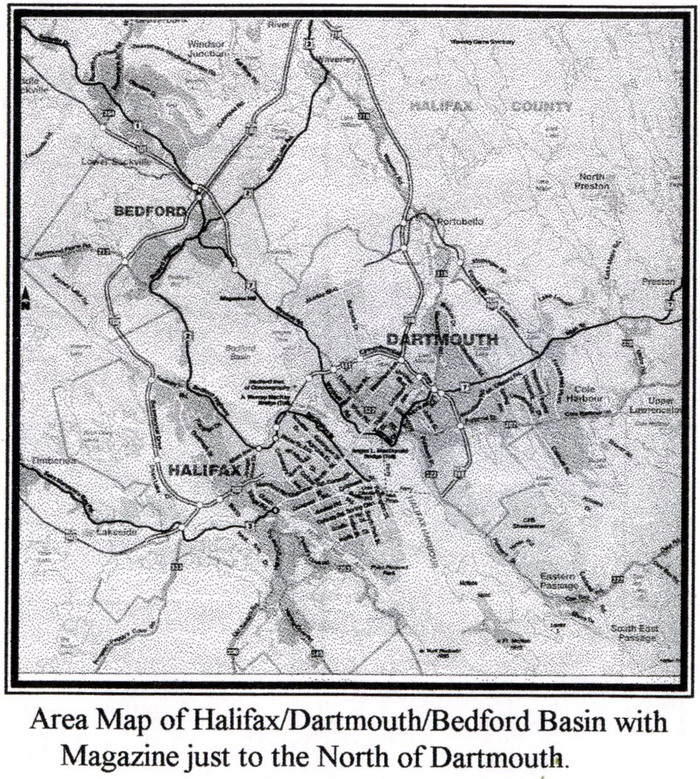

Although World War II continued in the Pacific, the war in Europe

ended in May, 1945. The Port of Halifax and Bedford Basin had hosted

transport ships, tankers, warships of all types, and merchant marine

cargo vessels, all supplying materials and personnel for the war

effort. They gathered here from all along the eastern seaboard of

the United States, as well as from other Canadian ports.

There was always the fear in this seaport community of a repetition

of the huge explosion of the 1917 ammunition ship collision, when,

on December 6, the Mont Blanc steamed up from the harbour

mouth where she had anchored overnight. Her cargo consisted of TNT,

tons of picric acid, and a deck load of benzol drums. About the same

time, the Norwegian steamer Imo chartered for Belgian relief

purposes, came out of Bedford Basin. At the Narrows, the two

collided. The result was the largest man-made explosion prior to

Hiroshima, with over 1,600 deaths recorded and the destruction of

thousands of homes.

Between this Halifax and the summer of 1945 there had been several

close calls, largely unknown to Haligonians. The V-E (Victory in

Europe) Day riots had caused strife between the service personnel

and citizens, but the City was working hard

to put that in the past.

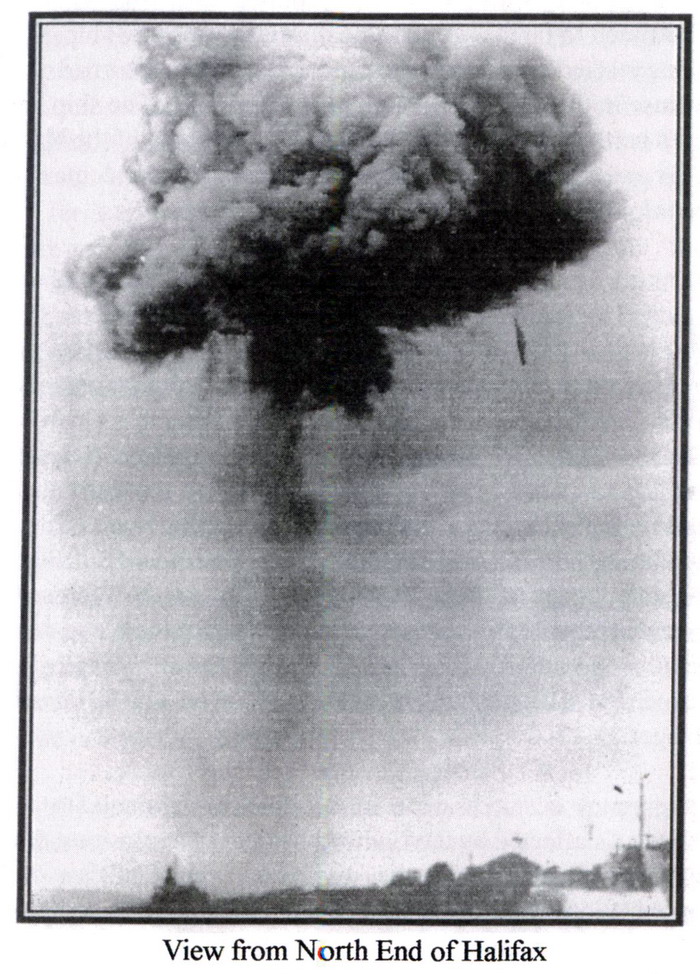

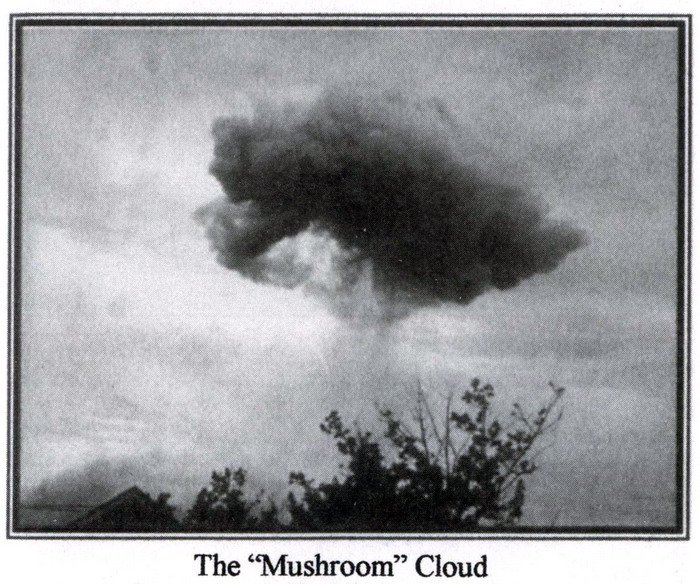

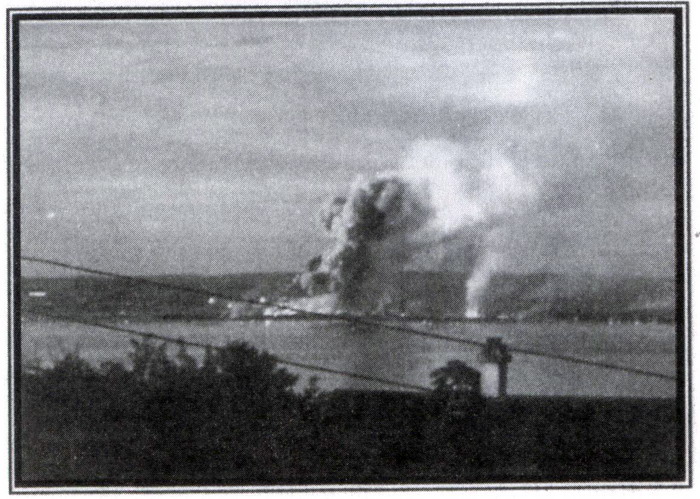

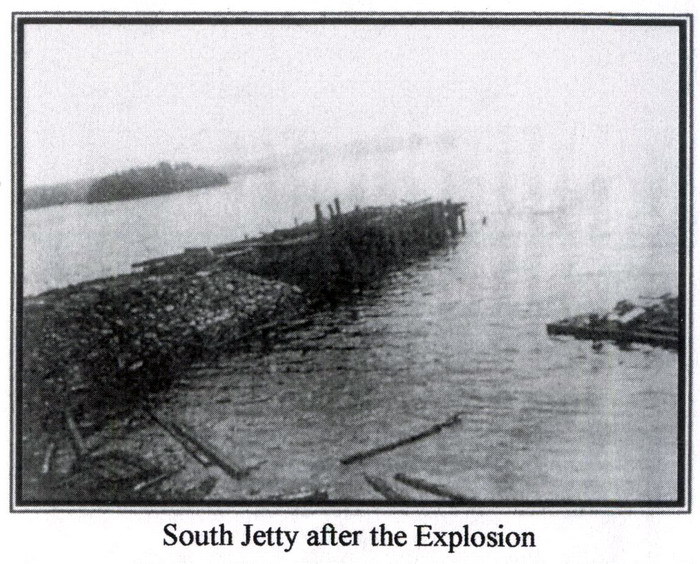

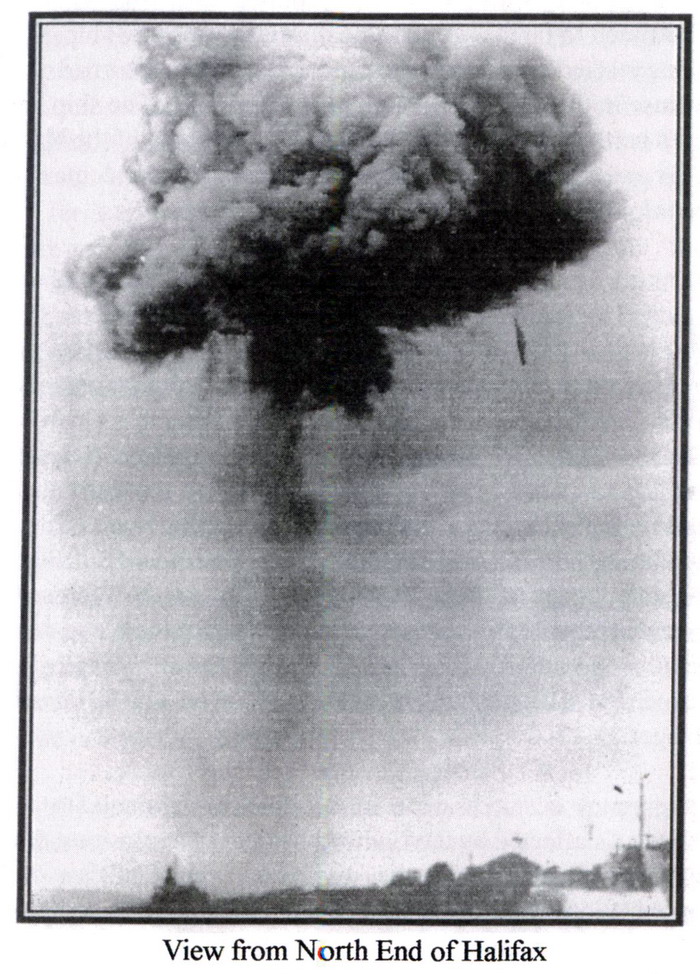

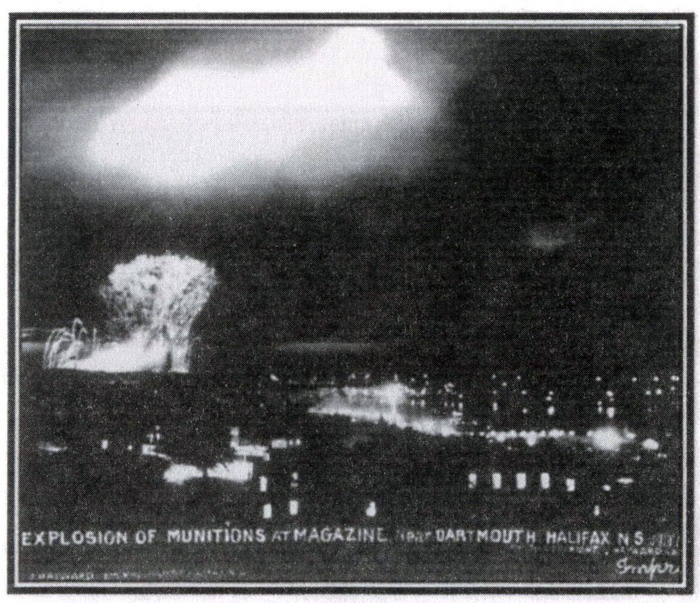

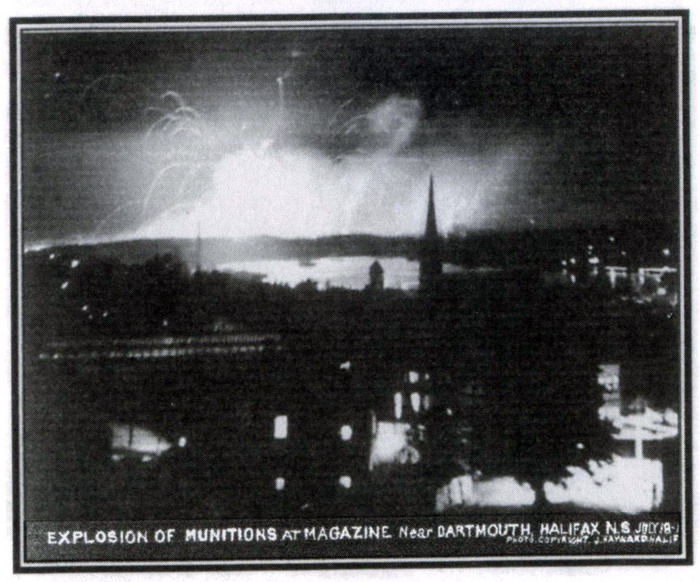

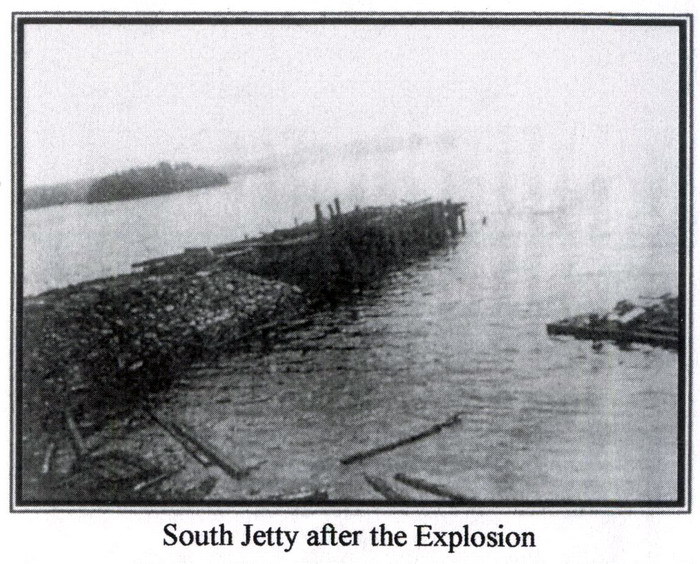

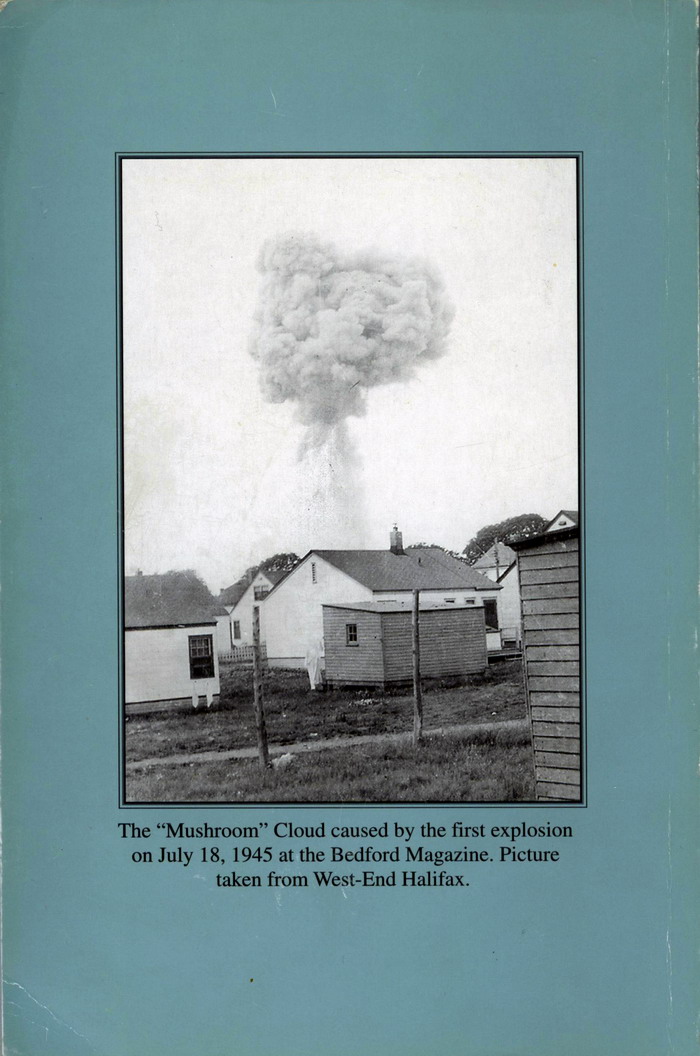

Trouble came at supper hour on

July 18, 1945, toward the close of what had been a hot summer’s day.

An ignition of a high powered explosive on a jetty at the Bedford

Magazine set off a series of fires, followed quickly by a big bang.

The ground shook for miles around, and the jetty and the barge tied

alongside disappeared. A high mushroom like cloud rose above the

Magazine that could be seen from distances well beyond the populated

areas surrounding Bedford Basin.

Minor explosions continued throughout the night, until approximately

4:00 am on July 19, when a huge blast shattered windows, shook

foundations, blew off roofs, and rattled walls of major buildings

throughout the area. The danger passed, but not before thousands of

refugees evacuated to the parks, protected streets, gardens, and

villages surrounding Halifax and Dartmouth. With limited roadways

leading from Halifax, particularly to the South Shore, traffic was

slow and tiring. Rescue and support systems were organized to give

whatever aid might be required, and to dispense sandwiches and

coffee. Children, adults, and seniors suffered not only physical

hardships but mental anguish and fear of what might yet come.

Fortunately only one patrolman was killed, but it was service

personnel who bravely, and without regard to their own safety,

battled the flames at the Magazine. They saved Halifax from an

explosion with the potential to wipe the city and its surrounding

neighbours off the face of the earth.

This book attempts to describe the events as they occurred and the

resulting investigations into the cause of the disaster. It draws on

written documentation, personal interviews, and archival research.

Chapter 1, Pre-explosion Conditions

In The Story of

Firefighting in Canada, Donal Baird wrote about conditions in

Halifax. The war in Europe had ended in May, 1945 and the City was

overcrowded and strained by its job as the key western terminus of

the Battle of the Atlantic convoy line. Long in fear of a repetition

of the colossal explosion of 1917, and with a couple of close calls,

the citizens and the Navy could now relax a little. The V-E Day riots

had caused bad feelings between the City and the Navy, but it was

now a time for return to normalcy. Troopships were bringing the

forces home, and naval vessels were coming home to be removed from

service.

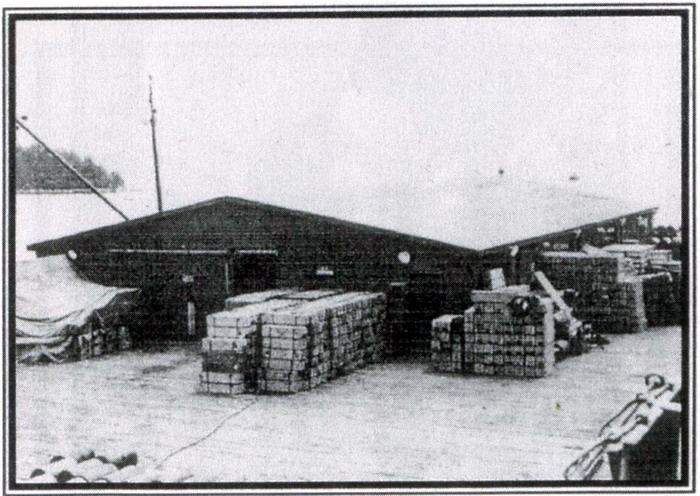

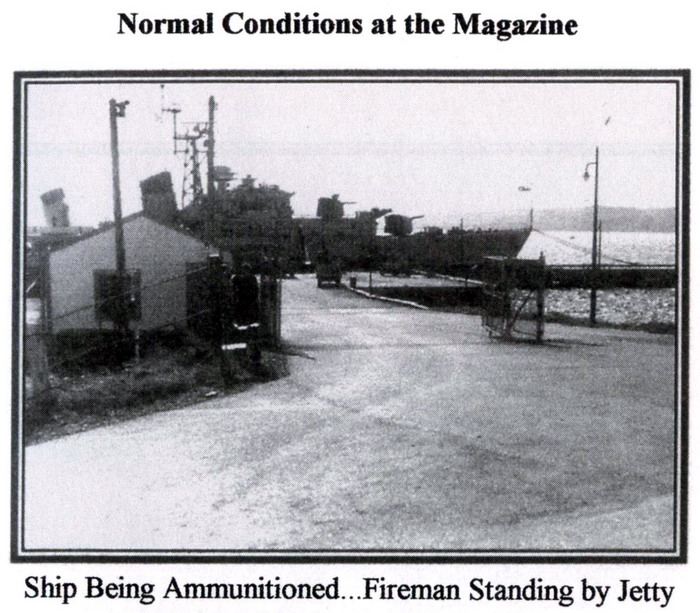

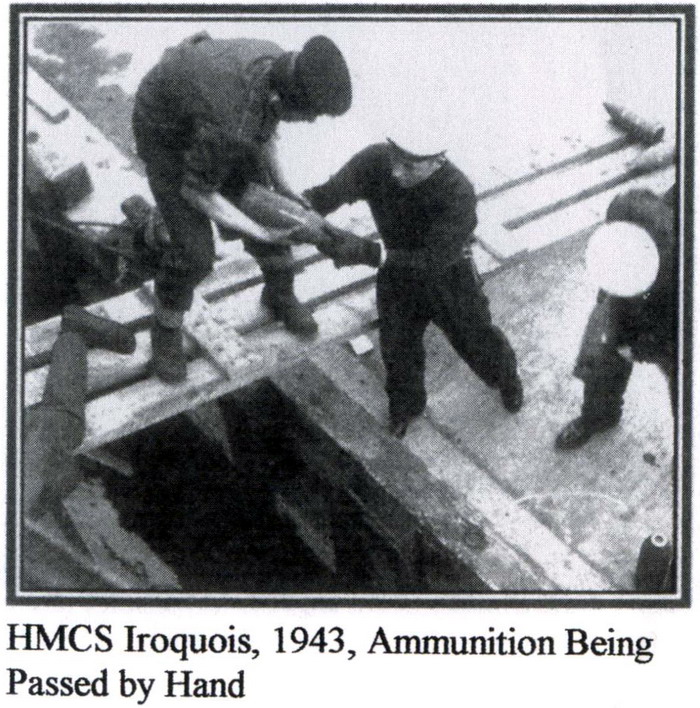

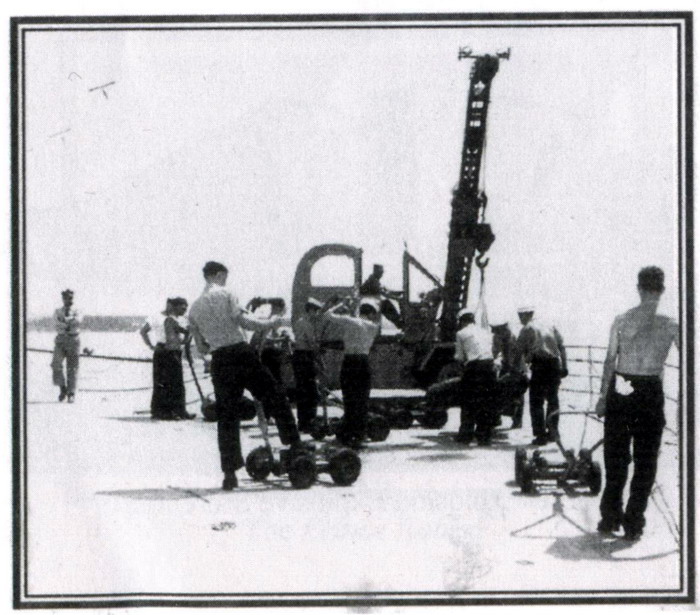

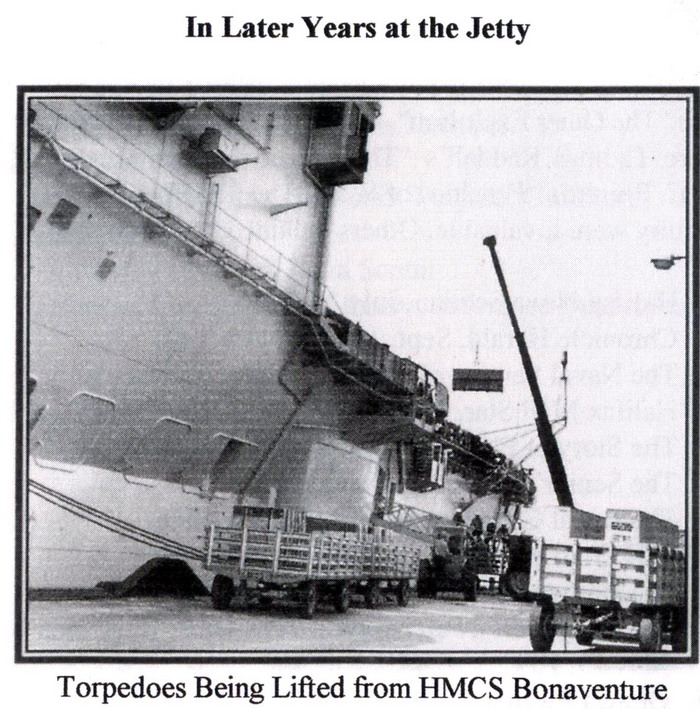

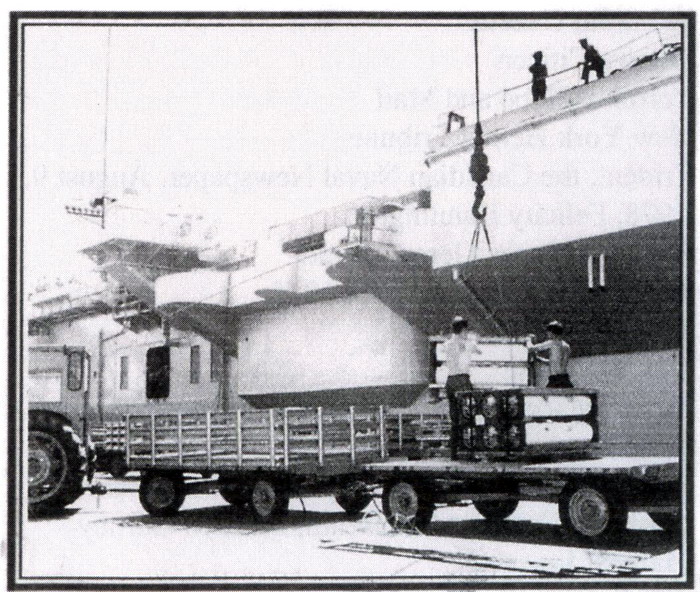

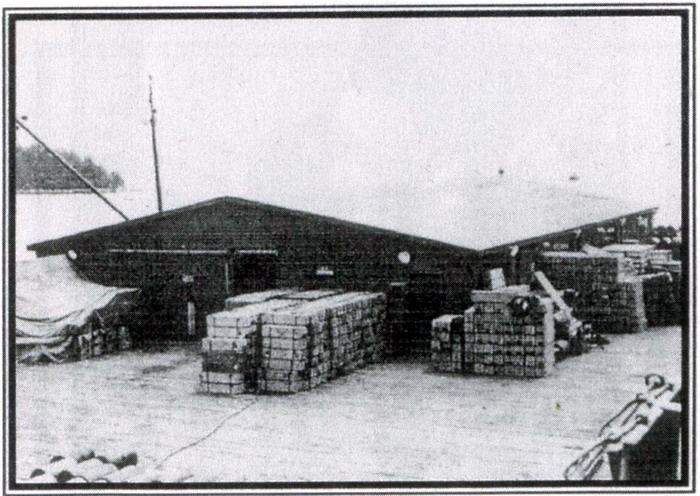

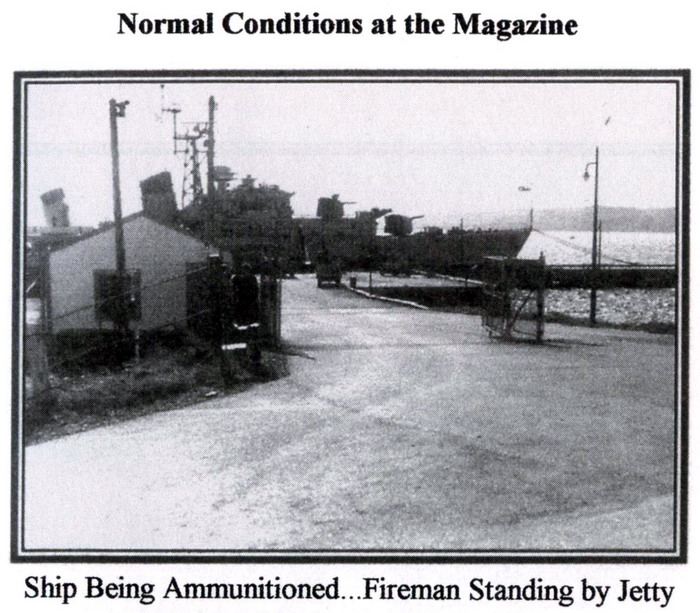

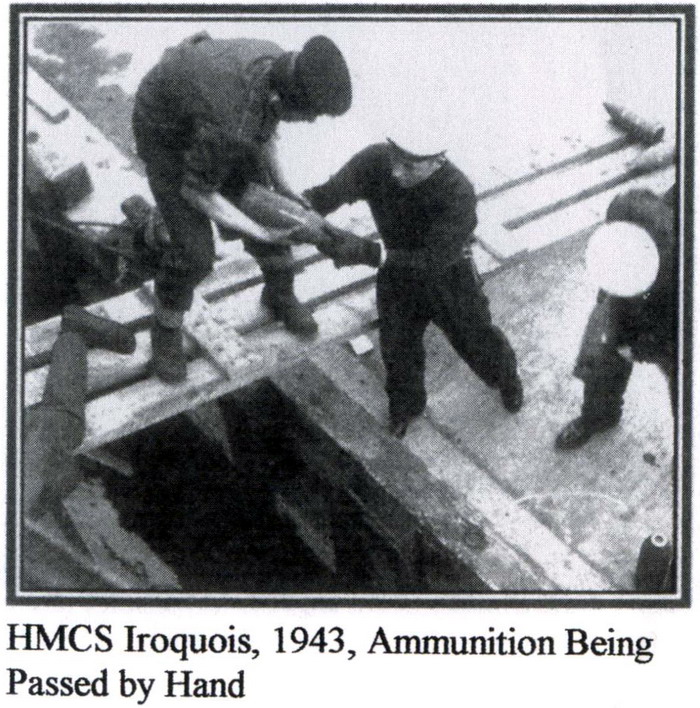

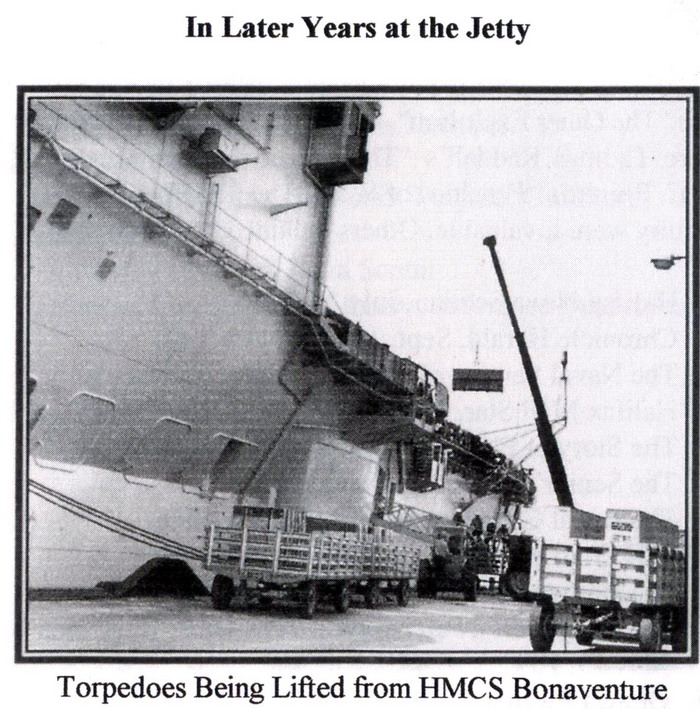

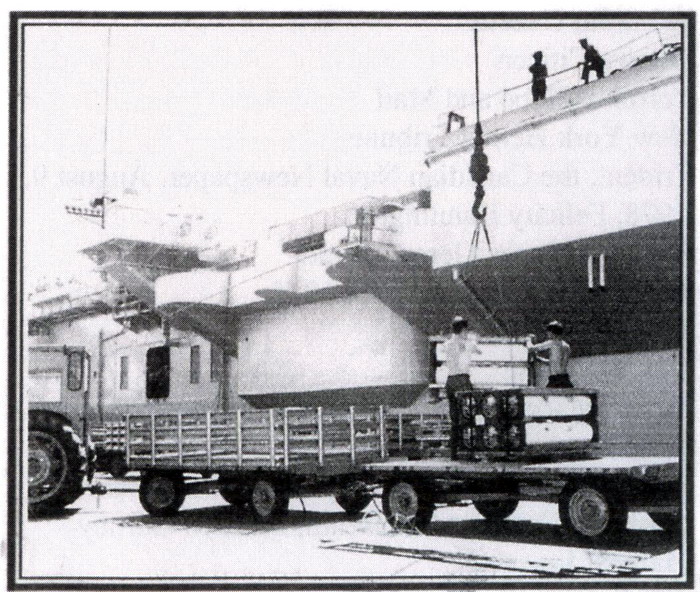

Before the many naval vessels could be decommissioned, the key job

was to de-ammunition them. This should have been a slow process, as

safety rules allowed only one at a time to unload its lethal cargo

on the jetty at the large ammunition

storage Magazine at Burnside, above Dartmouth on Bedford Basin.

However it was politically important to speed the servicemen home as

quickly as possible, and the regulations with respect to the

handling of ammunition were bent despite

protests. In an inordinate rush, three vessels’ stocks of ammo were

on the jetties at a time. The large, carefully designed magazines in

the rocky hillside on the wooded far side of the Basin were very

safe when the rules were observed.

The possibility of another explosion preyed on the minds of

Haligonians. ln the Halifax Mail Star, May 5, 1987, Alex

Nickerson wrote that prior to the explosion at the Bedford Magazine,

a cargo ship, the Trongate, was sunk by the Navy in Halifax

Harbour in April 1942. The 7,000 ton vessel had been loaded with

drums of highly inflammable toluene, and a quantity of ammunition.

It had been waiting in the Harbour to sail in a convoy bound for

England when fire broke out. In the forts, the gunners were hoping

they might be told to sink the blazing ship, but the more

knowledgeable among them knew that large calibre shells fired across

the water could ricochet and cause great damage and loss of life on

the Dartmouth side of the Harbour.

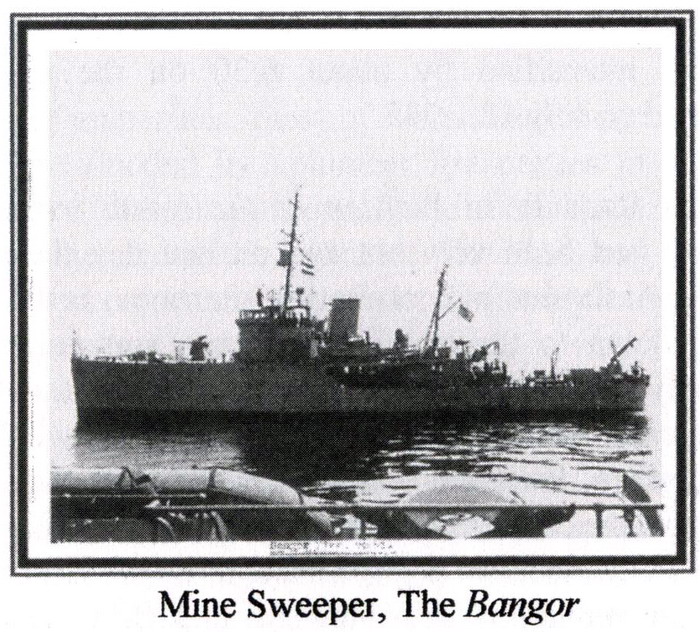

The Navy, when called in, fired round after round of solid shot from

guns of the minesweeper Chedabucto into the Trongate

below the water line. She went down without exploding between the

Department of Transport wharf and the Sugar Refinery.

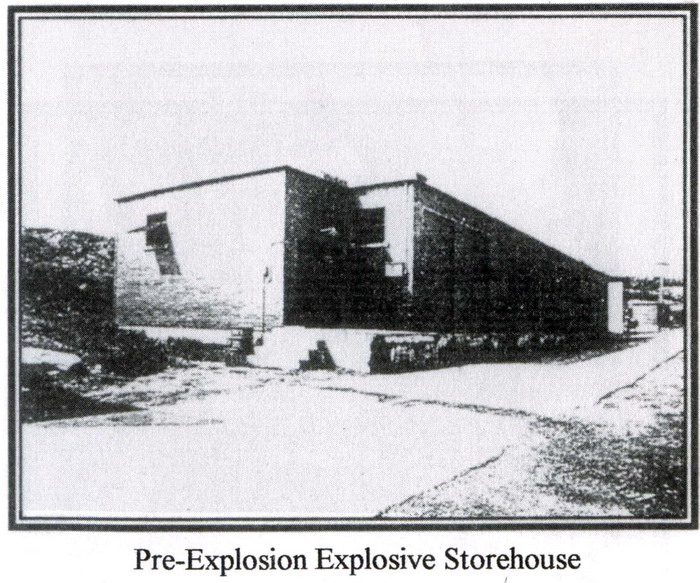

Although today the Canadian Ammunition Depot is perhaps an obscure

complex to most Haligonians, during the Second World War the arsenal

on Bedford Basin’s northeast shore presented a constant threat to

the City. As a repository for ammunition, depth charges, TNT

(tri-nitro toluene) waiting to be shipped to the front, it reminded

residents of the 1917 explosion. Not surprisingly, on July 18, 1945,

everyone assumed the worst.

Thomas Raddall in Warden of the North wrote, "After six years

of war, (on VE Day) Halifax was sacked by an unruly mob of its own

defenders and the dregs of its own population." Raddall went on to

philosophize that for complete irony all that remained was to blow

up the City with its own Magazine. The Navy had been busy calling in

ships and men from the Atlantic reaches, and preparing to switch its

efforts to the Pacific.

In Newfoundland, the St.

John’s magazine had been closed and its entire stocks sent to the

Bedford Magazine. Many ships had dumped off their stores and the

magazines were filled up. Still the ships came and the depth

charges, shells, torpedoes, pyrotechnics, and other lethal

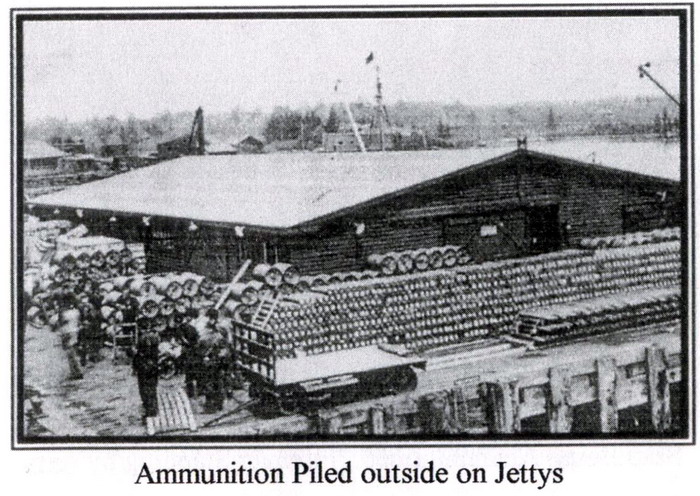

ammunition began to pile up in the open, even on the jetties. There

was great pressure on the Magazine personnel to get the ships

unloaded and away, so the rules were broken. For two months Canadian

naval craft of all sorts had passed up the harbour and put ashore

their ammunition.

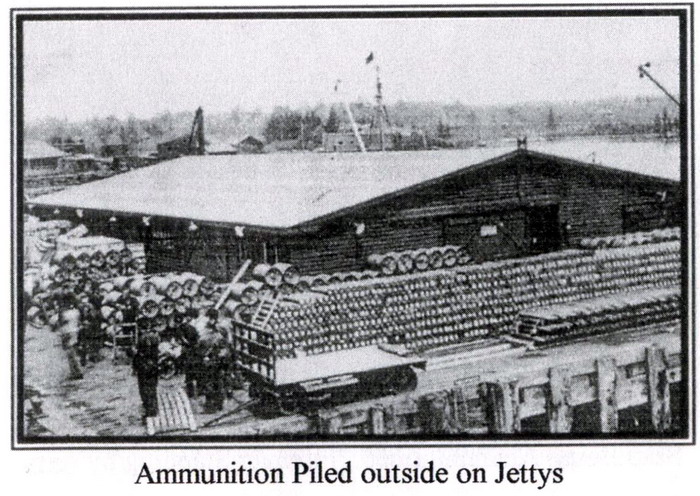

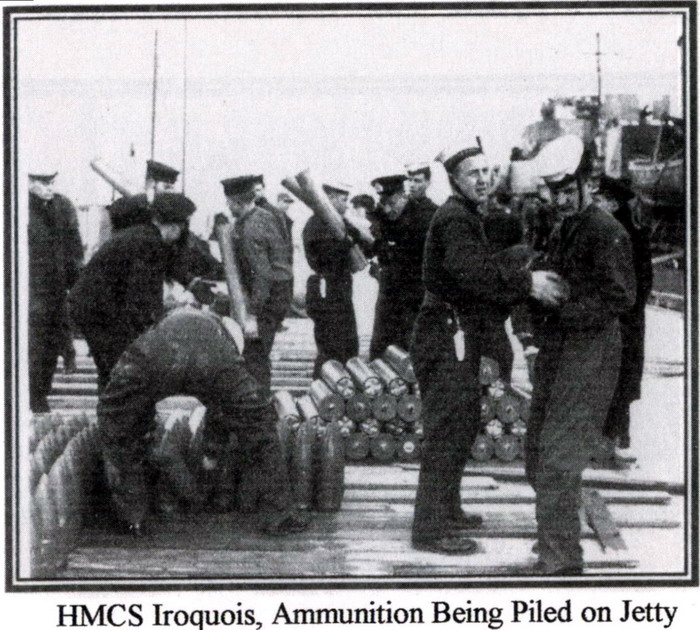

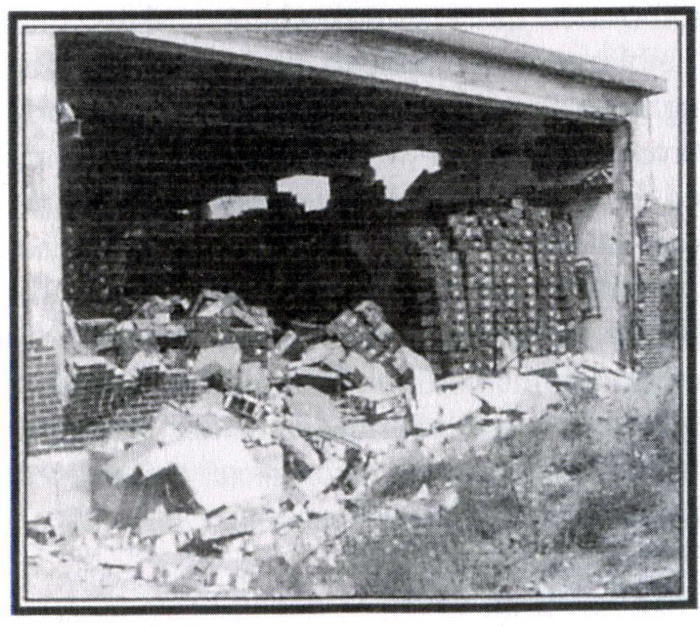

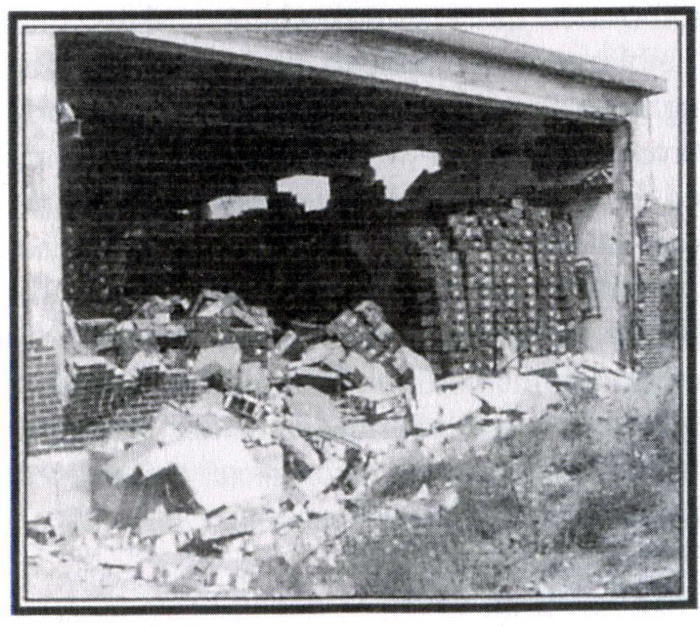

By July 18 the Bedford Basin

Magazine held an inordinate quantity of shells, bombs, mines,

torpedoes, depth charges, and other powerful materials. Much of the

ammunition was stowed away in the carefully designed and segregated

buildings, but of necessity a good deal had been stacked outdoors

for lack of storage space, and these dumps extended close to the

jetty on the Bedford Basin.

Gilbert Tucker wrote in The Naval Service of Canada,

"Throughout the war the magazines at Halifax handled a tremendous

quantity of ammunition and underwater explosive missiles for many

types of warships, as well as supplies for

defensively-armed merchant vessels. Located in Bedford Basin, the

magazines had been built in 1927 for the joint use of the army,

navy, and air force. Even before the war they had proved inadequate

for the needs of the RCN, and $130,000, a substantial amount in

those days, had been voted in the estimates for 1939 for their

enlargement. Nothing was accomplished before September however, and

during the early days of war, improvised shelter and open storage

had to be used."

As early 1940 the Naval Service had considered the provision of an

inland reserve magazine accessible by rail to all east-coast bases

in order to remove concentration of explosives at points vulnerable

to air attack. A suitable location was chosen at Renous, in

north-eastern New Brunswick, but because of the pressure of other

commitments on labor and materials, construction was not undertaken.

By the summer of 1943, over $1,300,000 had been spent on the

development of the Bedford Magazine, which by this time was used

exclusively by the RCN (Royal Canadian Navy).

Despite this relief the Halifax magazines continued to be so

overtaxed that it was not possible to comply with all safety

regulations. This was particularly true following the cessation of

hostilities with Germany, when numerous ships were being

de-ammunitioned.

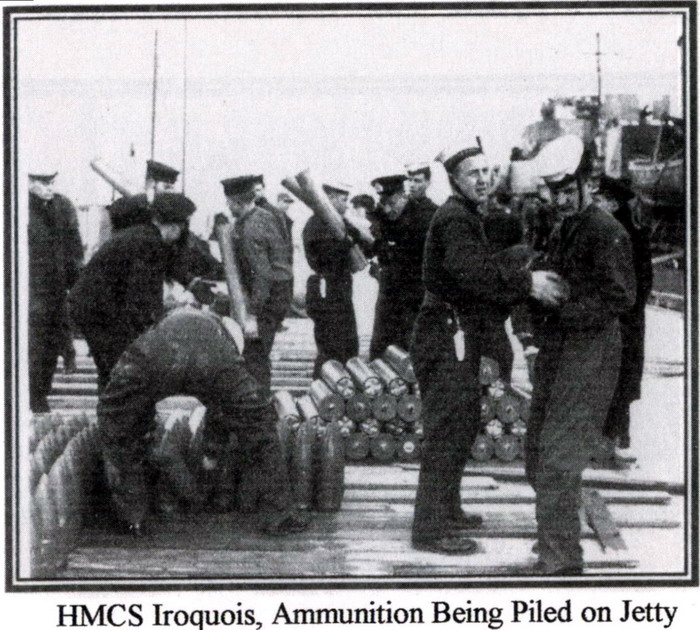

For another assessment of conditions, the Halifax Chronicle

carried an eye-witness account of the ammunition which had been

placed on the south jetty shortly before 5:15 pm, about one hour and

20 minutes before the explosion: A frigate was berthed alongside the

jetty and much of the ammunition piled there apparently came from

this ship. On the south side of the jetty, stacked six feet high,

were four and four-point-seven inch shells, cordite charges, fixed

ammunition, and about 400 "Hedgehogs" and some small arms

ammunition.

On the front of the jetty facing Halifax were approximately 80 depth

charges. Facing north were six-foot piles of small arms ammunition,

"Oerlikon" (medium calibre anti-aircraft projectiles) shells and a

considerable number of hedgehogs.

Along the north jetty were three loading barges and three lighters.

Contents of one barge and one lighter were said to be depth charges,

but the contents of the other four were not known. On the jetty was

a hut said to be stacked to the roof

with small arms ammunition, Oerlikon shells and hedgehogs. This was

the situation prior to the initial explosion. Halifax and its

environs were sitting on a powder keg.

Chapter

2, July 18 The Explosion and Evacuation

Trouble intensified by about 6:30 on the evening of Wednesday, July

18, 1945.

Thomas Raddall, in Warden of the North wrote, "The summer had

been very hot and on that day the heat was stifling. At the end of a

sweltering afternoon, as the city was sitting down to the evening

meal, an ammunition barge suddenly blew up at the magazine jetty.

The blast shook the whole metropolitan area and shattered

windows in Rockingham, Fairview, and the north end of the

city. The

report and the characteristic smoke cloud, a toadstool growing

swiftly in the northern sky, were like those of December 1917 when

the munitions ship blew up in Halifax Harbour and wrecked such

devastation and loss of life. This explosion seemed to come from the

same spot. There followed an uneasy silence, but the exposed dumps

had caught fire, and soon there began incessant rumbling and

concussion which went on for more than twenty-four hours."

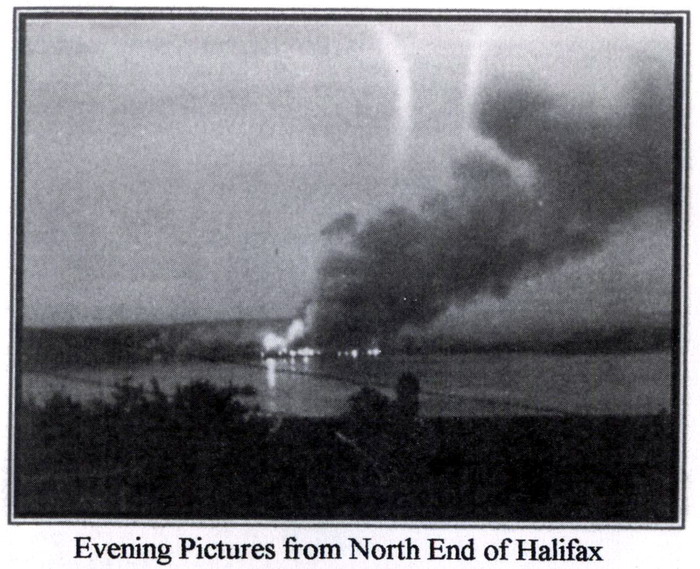

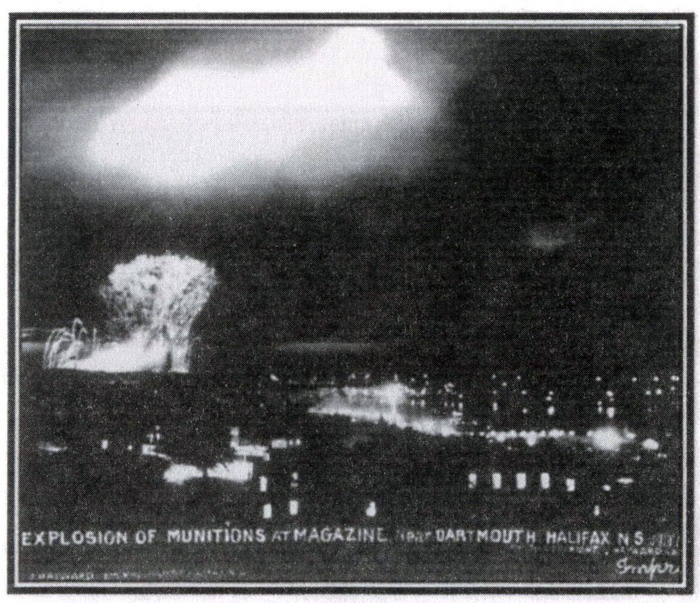

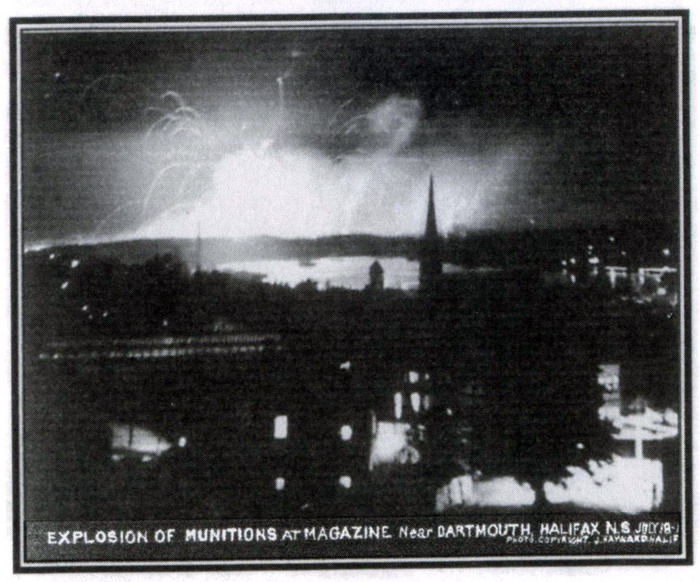

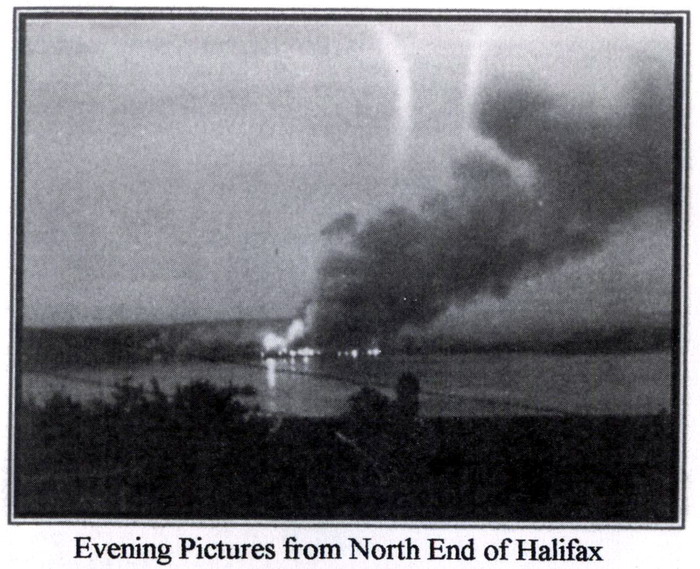

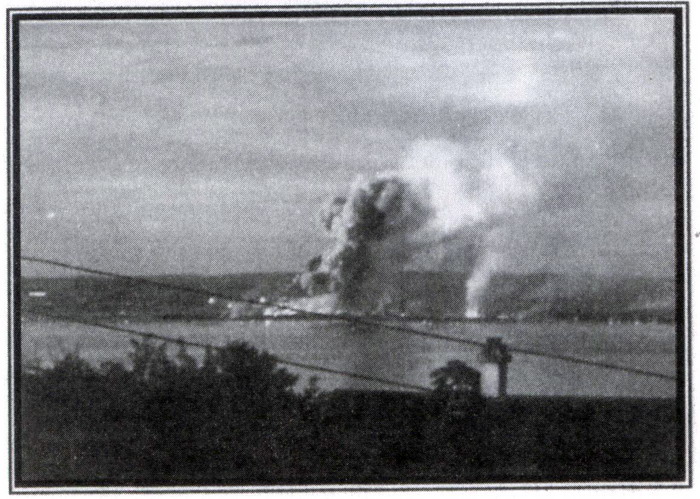

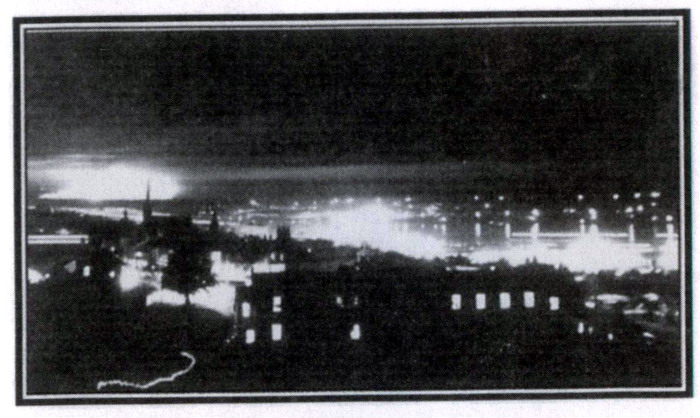

Raddall continued, "It was magnificent as the sun went down in a

fine red blaze that lit the whole of the west, and as the huge cloud

of dust and burning explosives arose and diffused over Bedford

Basin, it produced a tint that would have done justice to an

artist’s imagination. When the last daylight faded, the burning

magazine produced its own display, a vast golden glow across the

north, with crimson under lights, with sudden blue-white flashes,

and with fountains of rockets and star shells and flares."

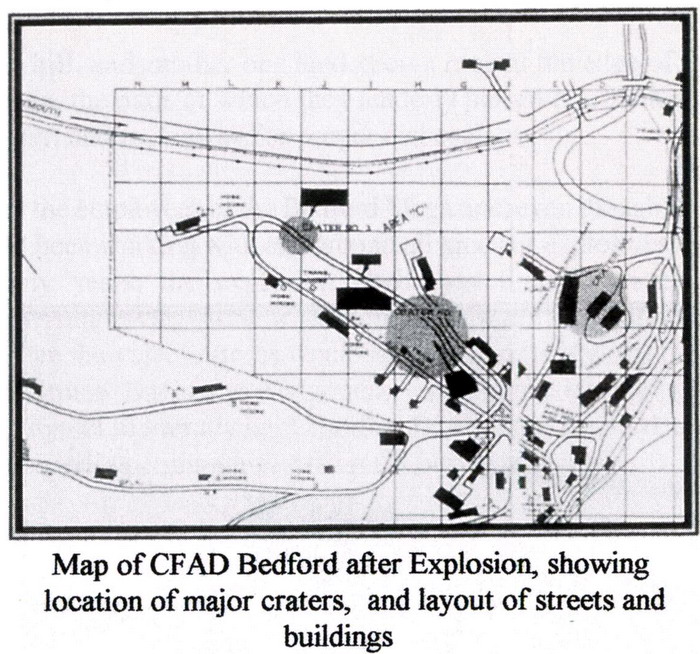

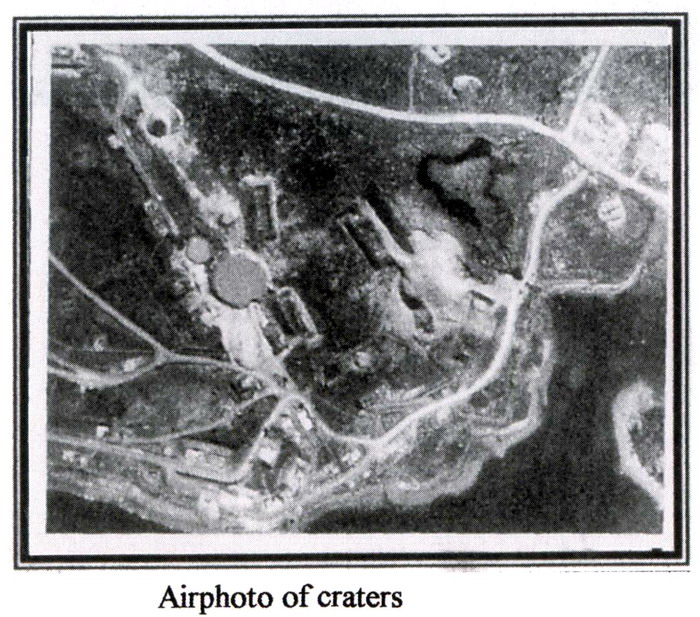

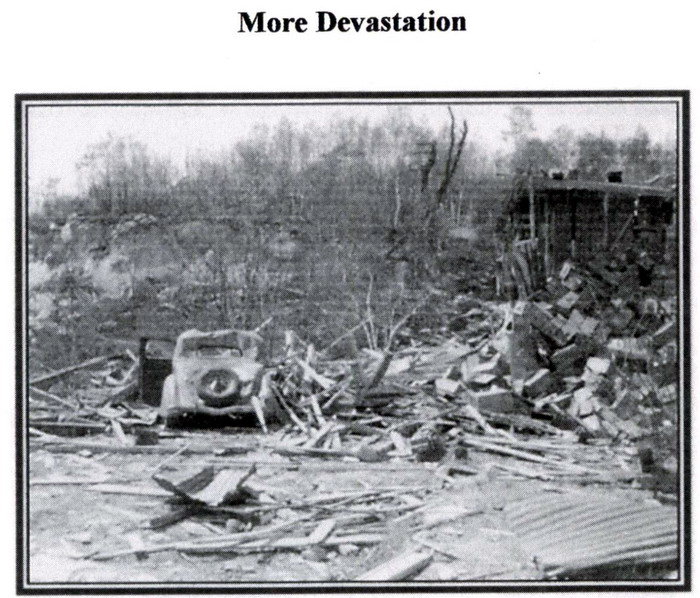

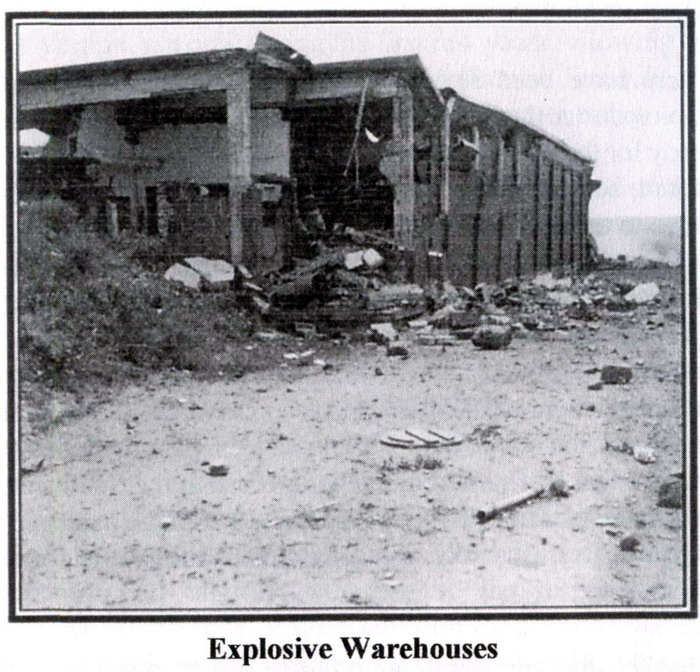

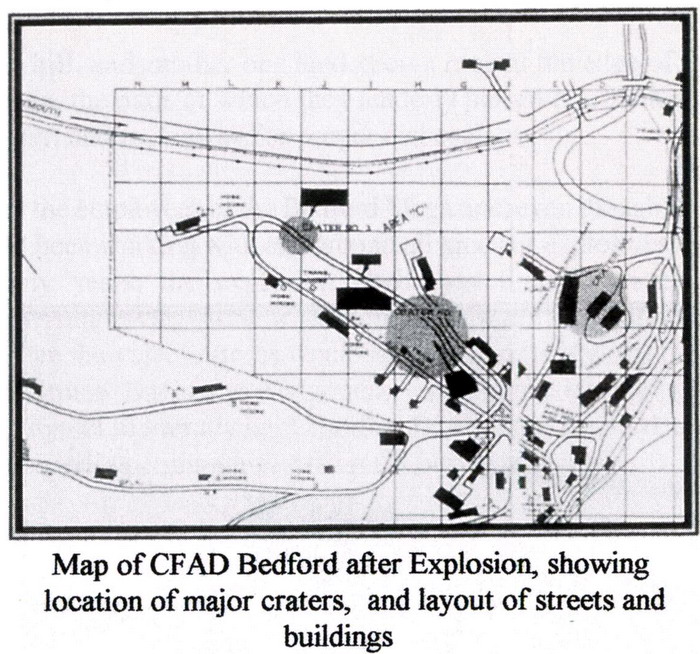

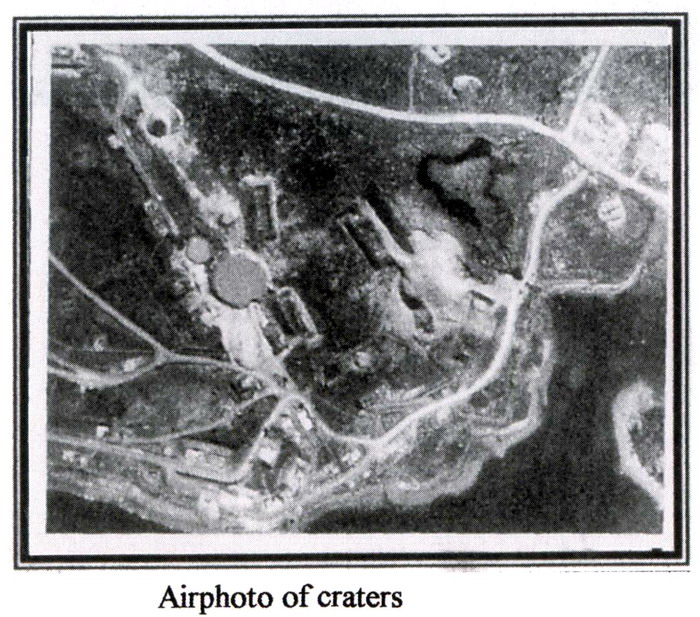

One third to one half of the ammunition dump was in ruins following

the explosion. This would cover an area of approximately 400 acres

and comprised for the most part the older section of the huge dump.

The newer magazines, most of which had been built since I939, were

flooded by volunteer fire parties to avert the possibility of

further explosions. These newer magazines were located in the area

to the northeast. The blaze had started in

the southwest corner and was gradually forcing its way to the new

section when it was finally checked.

Magazine superintendent Tom Underhill much later (circa l990-2000)

studied the explosion. He believed it was sparked by a stove left

burning in a barge. When the explosion went off at about 6:30 pm

daytime workers had already gone home

for the night, Underhill concluded that the ammunition on the jetty

exploded, setting off other stacks of ammunition. The first

explosion killed a night guard, and at about 7:40 pm, just an hour

after the original outbreak, there occurred a second explosion

almost equal in intensity. After that there was a continuous roll of

exploding ammunition of all kinds. The larger blasts could be

anticipated. At the flash of an explosion, "at the end of l0 seconds

we would get the report,

blast and rattle." Finally at about 10:00 pm there was one major

crack that really shook the solid steel and concrete federal

building, at least three miles as the crow flies from the Magazine.

The 30 foot square tower actually rocked back and

forth several times on its foundations.

Fairly heavy explosions occurred regularly until almost midnight

when a very heavy detonation took place. Cartridges, the majority of

which were four-inch, exploded intermittently well into the next

day. The blast blew out windows in Africville, a community on the

west shore of the Basin.

Again, in The Story of Firefighting in Canada, Donal Baird

related personal aspects of the explosion. He writes that Captain

Robertson, commander of the Naval Dockyard, was at dinner with his

wife at the Nova Scotian Hotel. He heard

the boom, and dashed to the top floor of the hotel, and looking

north, had his worst fears confirmed.

As soon as the explosion took place, naval firefighters, the only

people who knew the layout, went to work trying to control the fires

that were spreading in the dry grass and bush near the open piles of

ammunition. In no time, the nearby barracks burned down and other

buildings were blown flat. The water main had been knocked out and

its supply tank wrecked. Captain Robertson arrived at the Magazine

and had, just moved from behind a reinforced concrete building when

it blew up, and he was thrown into a pond.

Naval firefighters under Robertson’s command kept working, to

isolate the fires, in spite of the danger of flying bullets and

explosions that continued throughout the night. Occasionally men

were hit by shrapnel. A brush fire had been set at the railway

siding some distance away, where several boxcars of explosives were

set on fire and a tough battle for control was fought. Using

portable pumps and drafting water from ponds, Robertson’s men

achieved victory after several hectic days. Their wounds had been

patched right on the spot by a courageous nurse.

ln An East Coast Part ... Halifax at War 1939-1945, Graham

Metson quoted from the report of H.B. Jefferson, stored in the

Provincial Archives of Nova Scotia. At the time, he was, by chance,

looking through his binoculars and "right in front of my eyes

fireworks began to shoot into the air. They went up fast and not

very high in a sort of a sheaf of wheat formation, for all the world

like regulation fireworks. This suddenly mushroomed into a ball of

reddish flame, and a huge

ball of black smoke soared into the air above it, followed by the

hot wind of a concussion. Lesser explosions followed the main crash,

accompanied by dense clouds of yellow smoke, and occasionally the

acrid smell of burning cordite could be whiffed."

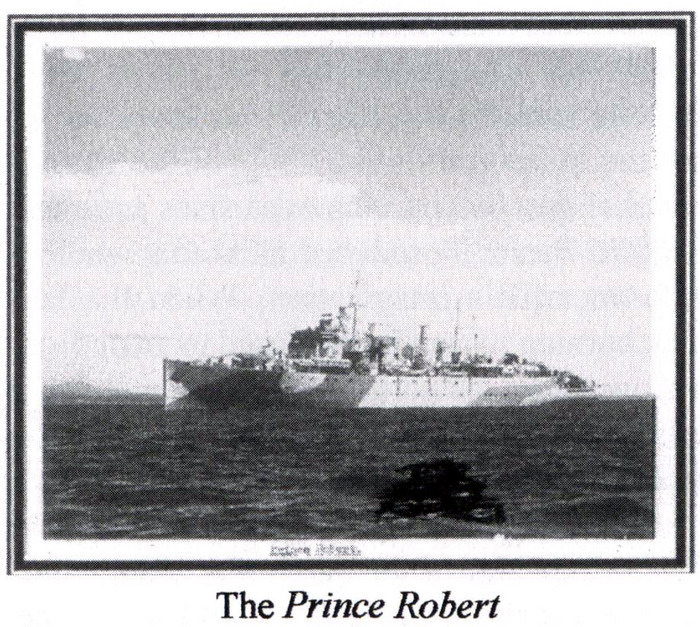

Almost before the first blast had died away, two large merchantmen

that had been in the Basin could be seen weighing anchor and coming

through the Narrows. Destroyers, submarines, frigates, corvettes,

minesweepers, and scores of smaller craft straggled out to the naval

anchorages east of George’s Island. Vessels under repair at the

Shipyards also were towed or pushed into the outer

harbour.

At the Union Coal Company, W.F.G. Fields, proprietor, was working on

his books when the building was shaken by the explosion. After the

first excitement had passed, he discovered the pen with which he had

been working was not to be found. Mr. Shield’s office escaped damage

probably due to the fact that the front door was open, also a window

at the rear, providing an escape as well as an entrance for the

implosion.

Action of a group of soldiers in averting a possible panic on an

Halifax-Dartmouth ferry when the first explosion came was being

praised by men and women passengers. Concussion of the ripping blast

lurched the ferry dangerously, and the majority of the passengers

feared the ferry itself had exploded. Witnesses said some passengers

were scrambling towards the rails with the intention of jumping into

the harbour waters when the soldiers stepped in. Ordering the fear

stricken passengers to stay where they were, the Army men explained

that the blast was not on the ferry, but at the munitions dump, and

there was no cause for immediate concern.

George Roscoe, who operated a canteen from his home about 300 yards

from the fire, was standing in the doorway of his canteen with his

wife nearby when the explosion occurred. He is quoted in Harry

Chapman’s In the Wake of the Alderney. "I was thrown to the

ground," he told a newspaper reporter. "Our home and the canteen

were completely wrecked. I got up and went out to help my wife to

her feet. We started to make a survey of what had happened when

smoke and flames surrounded us, forcing us to retreat." Roscoe, who

was slightly injured, managed to remove himself and his wife from

danger.

J. L. Smith, whose home was near Roscoe’s, also had a close brush

with death when his dwelling was destroyed by the explosion. "l was

first attracted to the disaster by what seemed like guns going off

followed by bright lights and rockets shooting high into the air. I

realized the danger at once because of my close contact with the

unloading of the ammunition from the corvette onto the jetty." Smith

was uninjured and remained in the area until he was forced to leave

by a military patrol.

Several women from Grace United Church were a few hundred yards from

the explosion as guests at the summer home of Dr. T. Courtney Browne

and his wife. No one was injured. Eight people from the area

however, were immediately taken for medical attention to a

re-enforcement camp set up in Bedford. Three of the men treated were

later taken to the Cogswell Street Military Hospital.

Within an hour of the first explosion, the navy had placed the

entire area from Ochterloney Street north to Bedford out of bounds.

The Town’s civil emergency association established emergency centers

at Dartmouth High School, town hall,

Somme Hall, the fire station, and Notting Park School. All available

firefighters, permanent and volunteer, were sent to the Magazine to

help. Then all available police officers were turned out along with

the military to assist the sick and infirm

and to establish order throughout the Town.

Fire raged, and reports that the largest munitions stock lay in its

path turned the Halifax Commons into a tent city, the Armouries into

a shelter for thousands, and Dartmouth into a ghost town. Service

personnel were on full alert. Ships were removed from the harbour,

civilians evacuated from areas adjacent to the munitions depot and

hospitals prepared for casualties.

Mr. Jefferson recalled that during the night, three more huge blasts

shook the Halifax-Dartmouth area, the loudest and most disturbing at

3:55 am when fire reached one of the small arsenals. "I remember

seeing the blazing red sky and hearing neighbours say, ‘the power

has gone off.’ Within ten minutes, as we hugged the ground, another

explosion punctured the dawn and most people feared imminent

disaster."

"Rumors, including one report by a naval officer that ‘no one in the

immediate area of the blast could have survived,' terrified the

citizens. Relatives called from ‘upper Canada’ to check on families.

I recall one relative asking if it were true that ‘l,200 people are

injured.' In Montreal, a hospital train outfitted with nurses and

doctors waited for the signal to proceed."

"Because adults and media reports compared the 1917 and 1945 blasts

with phrases such as, ‘reminiscent of l9l7,’ and 'the experience of

First Great War still a hideous memory,’ young people assumed that

disaster was inevitable. As rumblings continued, "I expected to see

dead people strewn along Barrington Street or floating in Halifax

Harbour."

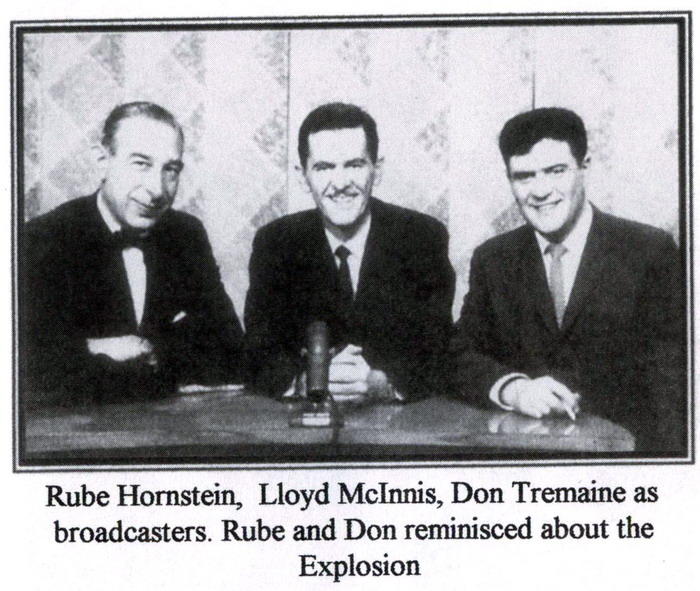

When the first blast from the Canadian Navy’s Ammunition Depot

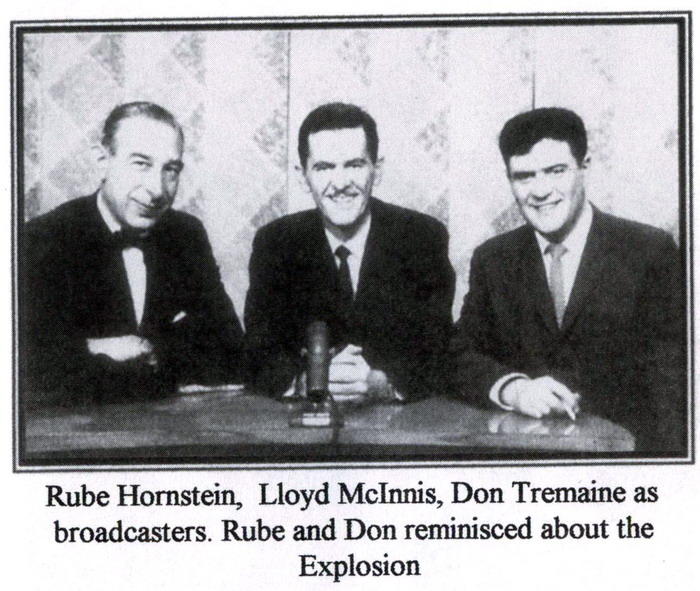

rocked Halifax on that Wednesday evening, July 18, 1945, CBC’ers

(Canadian Broadcasting Corporation staffers) were at the studios, on

outside duty across the city, or at

home. When they found out what had happened and what was likely to

happen, everyone who could struck out for the Sackville Street

studios.

As the evening wore on, and the situation grew worse, preparations

were made to keep the local transmitter, CBH, on the air all night.

Regional representative, George Young, kept in touch with the local

authorities by telephone and made

arrangements for special committees on the explosions for the

national hookup. News editor, Jim Kinloch organized a double night

shift in the newsroom to take care of the news reports and official

bulletins and warnings from emergency

headquarters, and the program engineering departments portioned out

the night’s duties to announcers and operators.

The news bulletins were handled very carefully. The full

significance of the situation was not minimized, but great care was

taken not to give cause for panic. During Wednesday night and

Thursday morning nearly one hundred items of one kind or another

were aired.

On July l9, the Halifax Mail reported on the events of the

day before. "Amid the calm and peace of a beautiful summer evening

an explosion from the Bedford Magazine came like a giant

thunderclap. From 6:30 pm onward, all through the

night, it kept on like a continuous roll of drum-fire. It was a

reproduction in flashes and flames and thunderous detonations

through a pall of fire and smoke, which all soldiers experienced

from mass guns firing along a battle-front. What began on the shores

of Halifax Harbour did not end with the first terrific blast. It went

on and on without a break, a continuous succession of detonations,

punctuated frequently by roaring blasts of greater volume, vivid

sheets of flame,

Iurid and awesome. And the inferno raged on all through the night."

Zen Graves was working at the Magazine Hill ammunition depot in the

summer of 1945 when it caught fire. Shells flared skyward, leaving

arching trails of smoke as they exploded in the woods or the waters

of Bedford Basin. "There were these

explosions going on all around, and you had to keep diving in the

ditch."

Bill McCall, a retired Mail-Star editor who was an army

captain at the time, remembered, "I went up to the Magazine and when

I got there I realized that terrible things were happening;

everything was a shambles. Everything was exploding from inside the

magazine. I didn’t know what was happening; shells were coming and

going like rockets."

The heavily bunkered design of the depot ensured that all of the

ammunition could not explode at once, but fed by dry shrubs and

bushes, the flames quickly spread and storage facilities were

destroyed. Only a l4-hour vigilance by military

and volunteer forces, and a lot of luck, prevented a major disaster.

Fortunately the fire never reached the main magazine housed at the

bunker where 50,000 depth charges were stored. "I don’t know just

what to think of the dire predictions about what would have happened

had the fire hit the main

magazines. Some of the experts claim everything would have been

levelled right down to Point Pleasant Park," Mr. Jefferson wrote.

Remarkably there were many less casualties than had been feared.

Henry Craig, of Windsor, Ontario, a naval seaman on watch that

night, was the lone casualty. He was believed to have been standing

on the jetty when the first blast occurred.

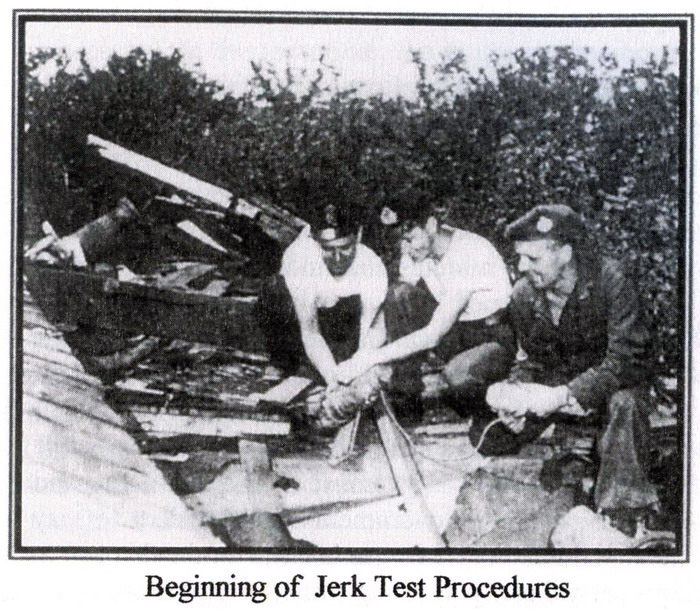

One of the few persons on the scene of the first explosion was Ted

Thompson, a student at Pine Hill Divinity College, who was working

at the magazine as an assistant timekeeper. Mr. Thompson probably

owes his life to the fact that he ran to the south gate to give the

alarm when the first outbreak of fire was noticed. He said that

while he rushed to the gate, Craig ran down the jetty toward the

fire.

The roll of injured was reduced to five, none of these seriously

hurt, all members of the Veteran’s Guard. Civilians seemed to have

escaped altogether in spite of the fact that in the areas nearest

the magazine, both in Dartmouth and Halifax, houses were tossed and

twisted, roofs crumpled, windows broken, sashes cracked and doors

caved in around them.

Naval firefighters, under the guidance of the ammunition foreman,

the only people who knew the layout, went to work to try to control

the fires that were spreading in the dry grass and brush near the

open piles of ammunition. The nearby barracks burned down; other

buildings were blown flat. Keeping clear of the shells and casings

they worked on the blazes constantly being set by flying ammunition,

risking their lives every minute.

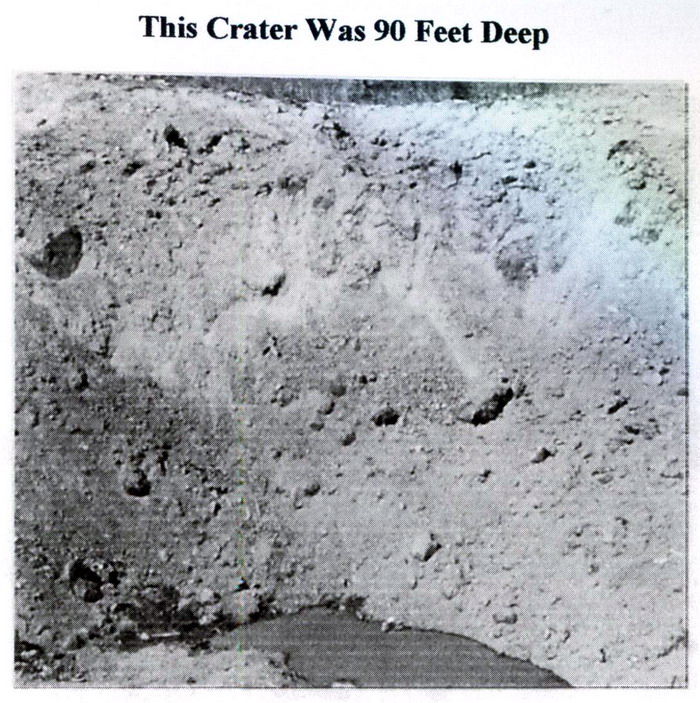

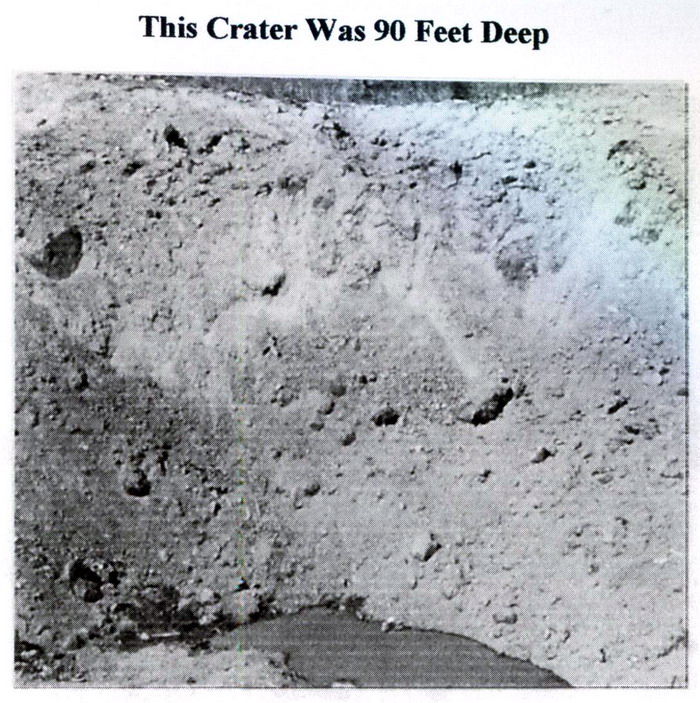

Among several big explosions, the largest came at 4:00 am, Thursday,

July 19, when a concentration of over 360 depth charges and bombs

went up, leaving a huge crater. The shock wave crossed the broad

expanse of Bedford Basin to ricochet through the streets of downtown

Halifax, breaking windows alternatively from side to side. The

booming, banging, and whizzing went on for several days, but the

worst was over.

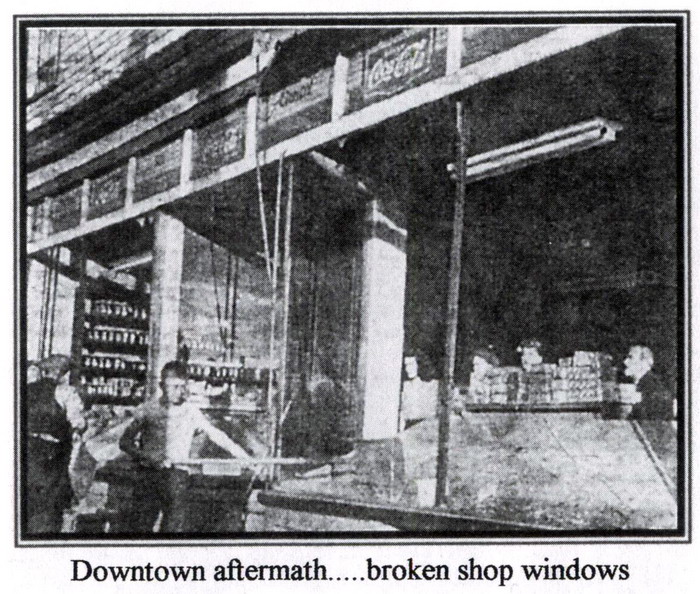

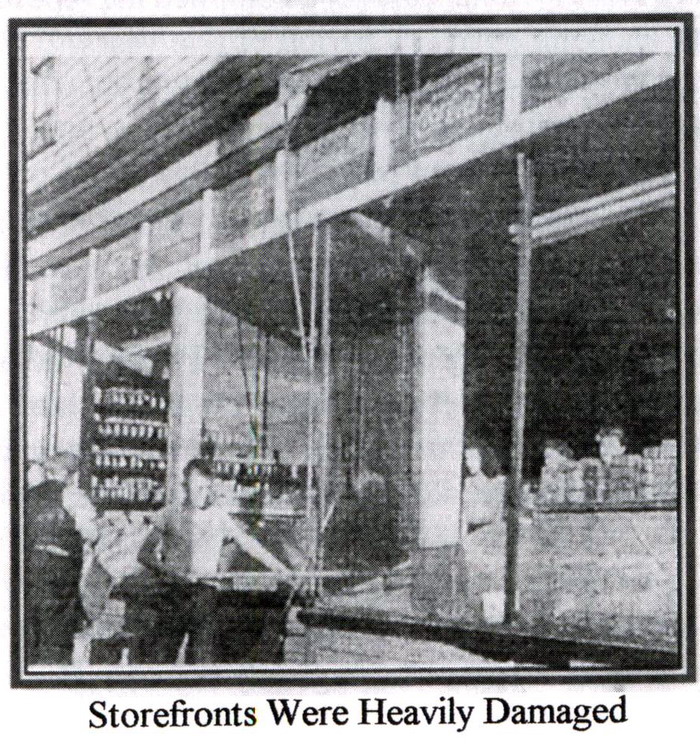

Major city damage had been confined to broken windows, dishes and

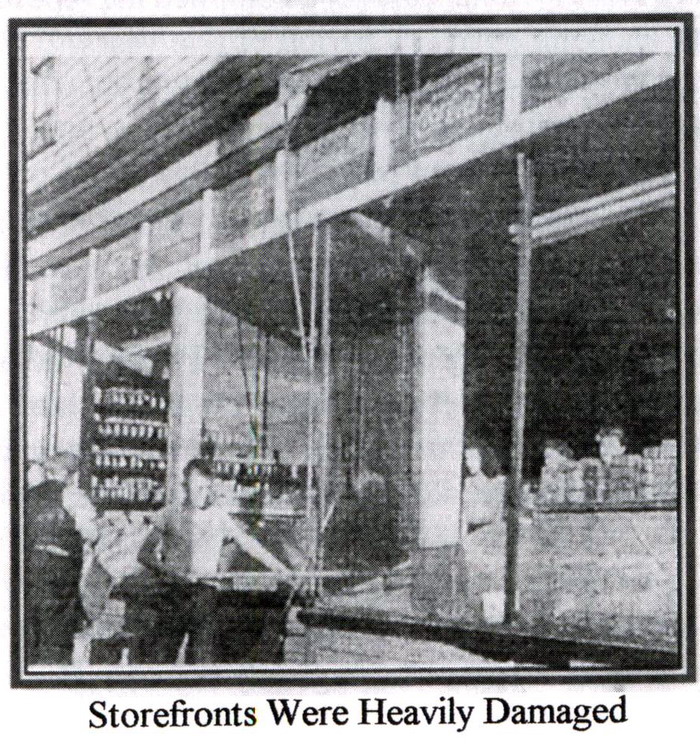

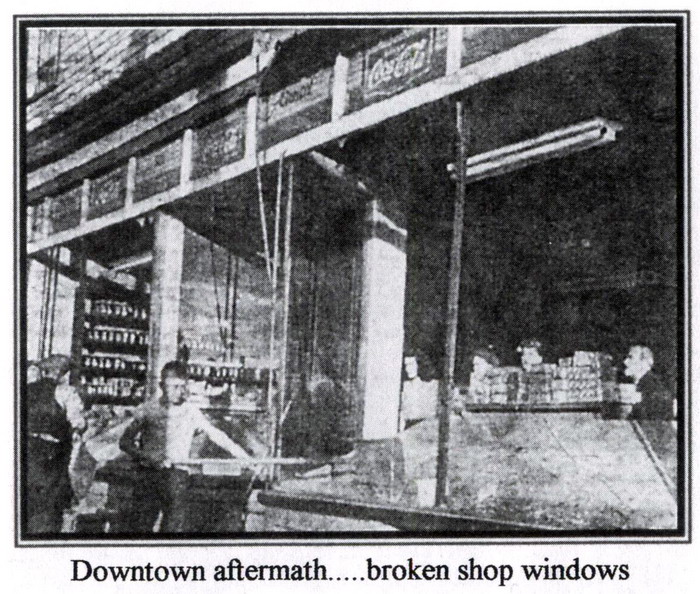

mirrors, and doors that had been blown out by the blasts.

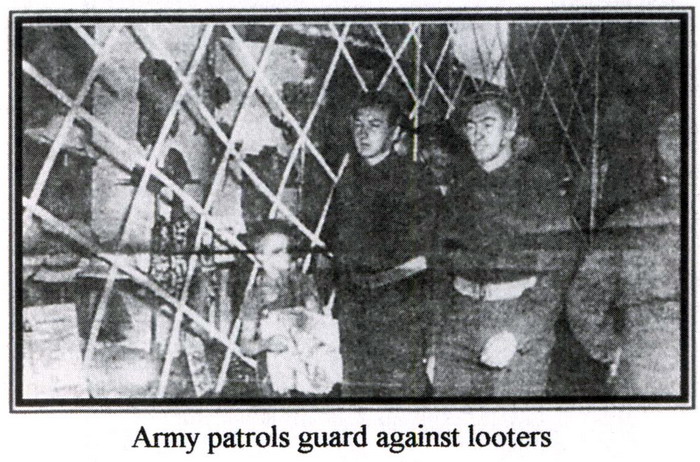

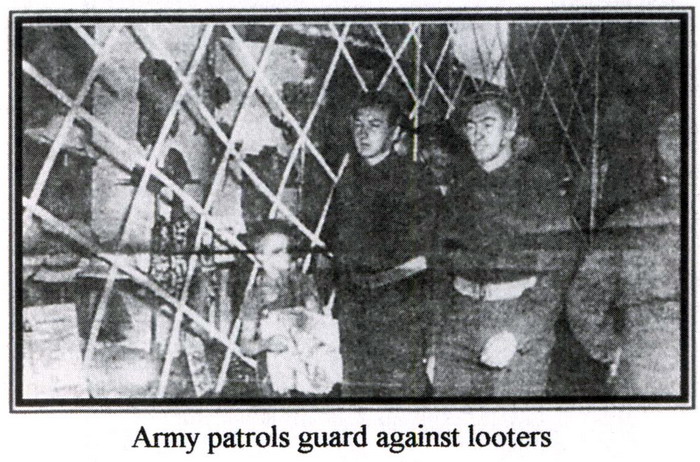

Surprisingly, looting was minimal, even though thousands had vacated

their homes and places of work.

Halifax churches were damaged and among them was the Zion AME Church

on Gottingen Street. Ten windows were blown out and much of the

plaster destroyed. The 105-year old edifice had only recently been

renovated.

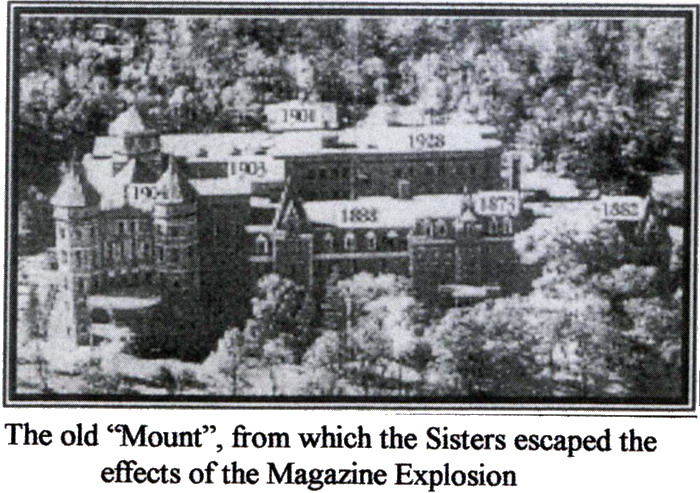

Extensive damage was caused to Saint Joseph’s Church on Russell

Street. The incident was not new to Saint Joseph’s, which had been

completely levelled in the disaster of 1917, and up to 1945, had

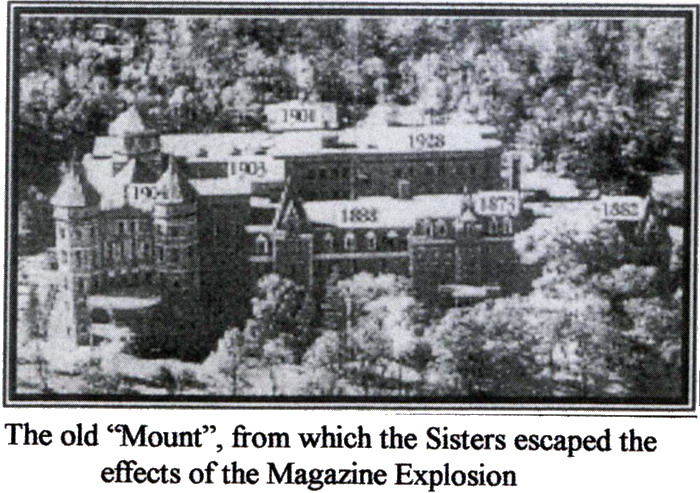

never been rebuilt beyond the basement. At Mount Saint Vincent

College, which faced Bedford Basin, the large glass dome of the

chapel was demolished.

Evacuation

H.B. Jefferson learned that orders had been given to evacuate the

whole North End as far down as North Street, opposite the Dockyard.

All Dartmouth residents, 10,000 or more, were being withdrawn to

A-25 Artillery Camp beyond the Eastern

Passage airport.

Patrols enforced the ban, and also kept watch for looting. With the

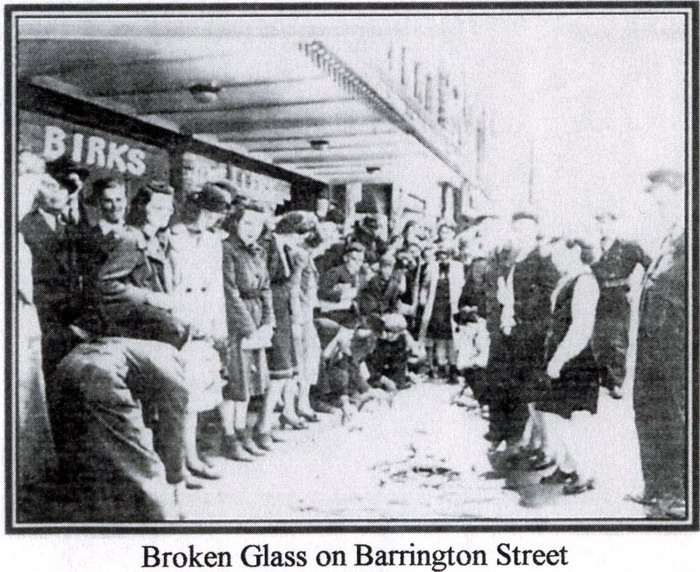

first blast, glass started shattering, the business, community of

downtown Dartmouth being especially hard hit. Many businesses in

Halifax and Dartmouth remained closed

during the day, and ferry crews, which had been working all night,

kept one ferry going.

During the early evening of July 18, Citadel Hill was black with

people afraid to stay within flying glass range of buildings. City

parks were crowded with people from the North End and elsewhere. The

Commons was packed with cars filled with people ordered from their

homes during the emergency. People wrapped themselves in blankets

and spent the night out in the open. Emergency shelters were set up

in both Halifax and Dartmouth. In the latter, naval authorities

declared "out of bounds" all North Dartmouth from Commercial and

Ochterloney Streets intersection to Bedford through Tufts Cove and

Burnside. Some 2,000 people from the area were moved to the army

artillery training center at Eastern Passage.

Just before midnight, WRENS (Women’s Royal Naval Corps Personnel)

were evacuated from HMCS Stadacona and Peregrine, and hundreds of

them bedded down in Point Pleasant Park, navy trucks bringing down

their cots and bedding. Later they were transferred to the

Gorsebrook barracks.

Police co-operated in the evacuation Wednesday night when they

issued certificates authorizing service station operators to provide

gas long after hours, filling the tanks of cars parked with women

and children eagerly hoping to be taken from the danger zone.

At 9:00 pm July 18, Naval headquarters broadcast a warning that all

people living between North Street and Bedford Basin should evacuate

their homes at once. Later the warning was extended to all living

north of Quinpool Road, more than half the City.

Some of the refugees went towards the south end of the City where

the woods of Point Pleasant Park offered space and shelter, but most

headed out of the peninsula altogether. Here rose a problem

envisioned during the war. The Halifax

isthmus was a perfect bottle-neck. Only two roads led out of it, and

the main one ran along the Bedford Basin shore, fully exposed to the

blasts from the burning Magazine. The whole evacuation had to be

made by the single road past the head of the Northwest Arm. Soon a

solid mass of vehicles, ten miles long, crawled slowly to the west.

Some of the cars and trucks carried mattresses, and even a few

chairs lashed to the top or rear of the cars. There were baskets of

food, blankets, and luggage of all sorts crammed with family

valuables. Along the roadside trudged a multitude on foot, many

pushing perambulators, pulling hand carts, carrying babies, or

leading little troops of wondering children.

There was no panic. The faces were serious, the voices low. In the

crowd there were many soldiers wearing the stripes of long service,

and now leading their families away from a scene such as they had

often witnessed across the sea.

But thousands still remained in the North End, refusing to abandon

their homes. These threw open windows and doors to save them from

air blast, and went outside, sitting on pavements, in back yards and

gardens, to watch the fireworks.

From time to time a major explosion sent a huge yellow flame

upwards, and all threw themselves flat, counting the seconds aloud

and waiting for the blast.

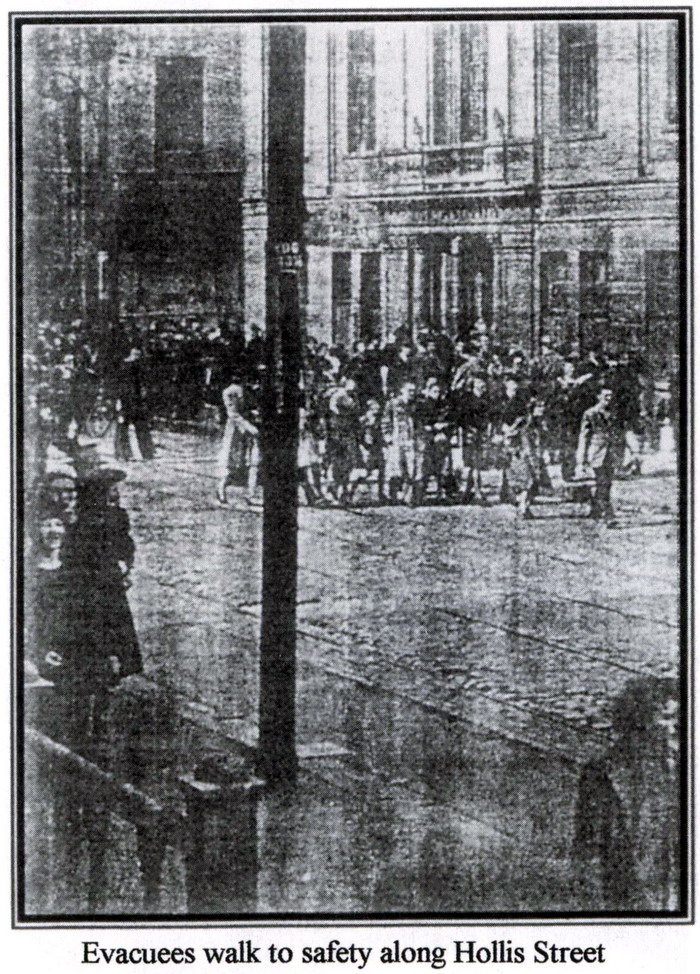

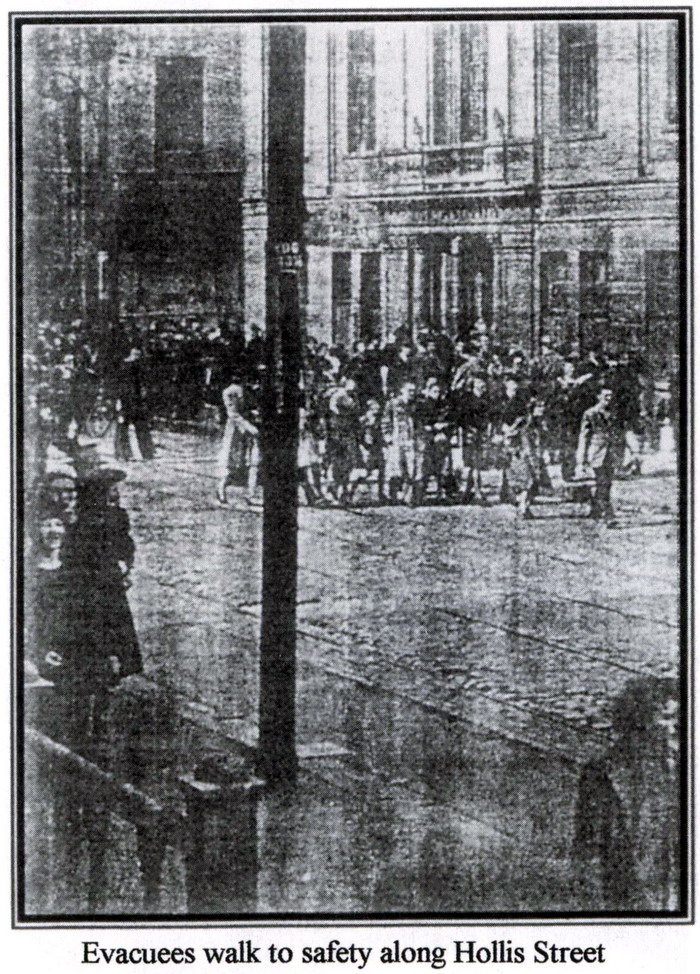

Newspaper pictures showed a variety of Halifax shots. Swinging in a

hammock slung between two trees in Grafton Park, a three-month old

baby caught some sleep while the rest of the family lay on the

grass. There was little sleep for a

group at the Public Baths on Horseshoe Island. Clutching bedclothes

and personal effects, refugees from the Explosion walked along

Quinpool Road, and home was anywhere you could make it, some taking

refuge on the back of a truck. There were coffee and refreshments at

Francklyn Park supplied by the Red Cross. At the Navy League

Recreation Center, over 1,000 sought refuge on the spacious grounds.

Staff members led in the singing of hymns and songs.

Volunteers donated blood at the Cogswell Street Military Hospital in

the event of heavy casualties.

Naval and army vehicles helped evacuate people in the Bedford area.

The RCAF sent a convoy of trucks from the A23 Training Center at

Eastern Passage to help evacuate people from Dartmouth. In addition,

hundreds of people drove or walked to Waverly or Eastern Passage.

The Halifax Herald was quoted in the Senior’s Advocate,

June 1986, "Every house for miles around the Magazine area was

ordered to be evacuated as military and civilian police took action

to avert a greater disaster should the larger

ammunition dumps blow up."

Bedford immediately became the scene of the greatest military

activity ever witnessed in that area. Sunnyside, the popular dine

and dance centre, was taken over by the Army. ln nearby Tuft’s Cove,

windows and doors crashed in after the

First explosion and people streamed from their homes to get what

protection they could find close to the ground. Within a few minutes

orders came from police and naval headquarters closing the area to

all who approached it.

Later those orders were extended and applied to all Dartmouth from

which poured practically every resident as places of business and

houses alike were evacuated.

The same situation was developing in Halifax, where wild rumors

spread, fortunately without causing panic. Whole families by the

thousands rushed to the Commons, Public Gardens, Point Pleasant Park

and the Dingle. Their numbers

were exceeded possibly only by the throng which filled the Shore

Road toward the Head of Saint Margaret’s Bay. All movement out of

the City toward Bedford was stopped early in the evening, and

residents surrounding the Basin were

ordered from their homes.

Police told a Mr. Barnes, his wife and their three children, to stay

in a nearby field, away from the dangers of a collapsing home. Mr.

Barnes said his family was sitting under a large tree, "when all of

a sudden a big piece of iron took a branch off over my head and I

said, ‘the hell with the bloody police. I ain’t staying here’. He

ran with his family to safety further south. "I carried my daughter.

She weighed about ten or fifteen pounds when I started and by the

time I got to Preston Street I thought she weighed a ton."

The Barnes family ran to a relative’s house. There was no room for

them, so they were taken in by a neighbour and waited out the night.

By 9:00 pm, July 18, a large convoy of army trucks left A-23

Training Centre for north Dartmouth. There more than 2,000 residents

were loaded on board and taken to the military base in Eastern

Passage. The entire facility, including the hospital and medical

staff, was put at the disposal of the evacuees. Several people

arrived in a state of shock, and some had to be treated for minor

injuries. As many as 10,000 people were evacuated from Dartmouth and

the surrounding area that night.

Anne Rockwell Fairley recalls: "Citizens were advised to spend the

night outside. Haligonians carried chairs, tables, afghans, blankets

and pillows to their lawns and driveways. Many prepared to sleep in

the middle of the street. Everyone

tried to place himself as far away as possible from windows and

doors. Neighbors chatted, tea was made, and many of us played kick

the can. Thousands climbed Citadel Hill and thousands more relaxed

on the grass in the Public Gardens."

Dartmouth was hard hit by the blasts. The Town suffered immense

property damage and hundreds of casualties. Evacuation of

practically the entire civilian population from the Town, Tufts

Cove, Albro Lake and adjoining areas was carried out. Hundreds of

members of the armed forces, the entire personnel of Dartmouth Civil

Emergency Association, town and auxiliary firemen and countless

others worked heroically to relieve the suffering and distress for

well over ten hours. In fact, the majority of them remained on duty

at the town hall, or in patrolling the streets, operating the bus

fleet, motor trucks and cars, until long after the break of dawn.

Pitiful scenes were enacted following the first terrific blast, as

all the families from the stricken area and beyond it started to

leave their homes, mothers carrying infants, when other

transportation was not available. Following the first blast,

scores of motor cars sped to the Naval Magazine arriving before time

permitted for any organization to function. Wild confusion reigned

for a time until the Mounties, Shore Patrol, and other members of

the armed services, along with the

Dartmouth police, newly organized service police, ARP (Air Raid

Protection) workers, with the generous co-operation of hundreds of

private citizens, got in complete control.

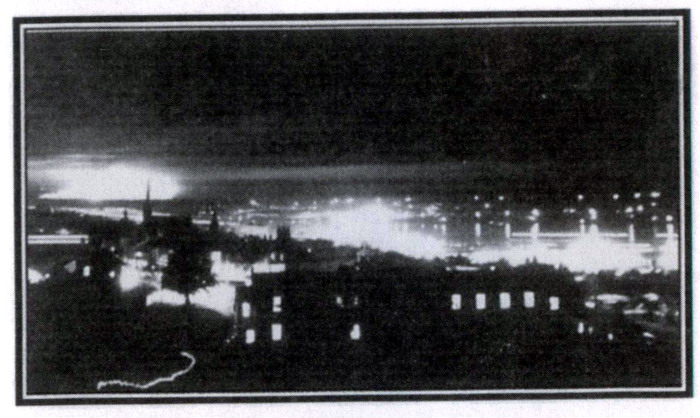

Five kilometres away in downtown Halifax, thousands of people,

forced from their homes either by a military evacuation order, or

scorching heat, began to gather on Citadel Hill to watch the

spectacle. In the meantime thousands were being evacuated from the

communities that ring Halifax Harbour and Bedford Basin. Most spent

the night variously out-of-doors in the open, in fields, on the

Commons, at Point Pleasant Park, in the Public Gardens, on Citadel

Hill, at Woodside, and in many other locations away from the blasts.

Peter Richards described the

situation in Dartmouth. "In the midst of the confusion, I managed to

hitch a ride in the back of a half-ton truck which was heading out

of the immediate danger area. As we drove slowly along, I noticed my

friend walking along the side of the road, so got the driver to stop

I and pick him up. We were left off at my parents camp, whereupon I

quickly checked to make sure all were safe. Then I ran down the hill

and found our neighbour’s cottage abandoned. I eventually made my

way to the SF (Semper, Fideles) grounds and was vastly relieved to

find my sister and her son along with a number of other cottagers.

The SF grounds were not in direct line with the magazine and was

away from falling objects and unstable structures. Bullets

were still firing and the popping continued unchecked. At this

point, we had no means of transportation out of the area, nor any

idea of the dangers that faced us."

"While we were at the SF grounds, we witnessed extremes of human

reaction, from the selfish to the selfless. One car with the back

seat unoccupied drove by without a glance to those needing

transportation. Then another car came into the field and picked up

some of the most needy, while shortly thereafter a half-ton truck

came along and gathered up the remaining cottagers, and we headed

off toward Dartmouth. The road was crowded with pedestrians and

vehicles, all heading away from the magazine as fast as conditions

would permit. As we drove through Tufts Cove, I caught a glimpse of

our dog, Bingo, running along the side of the road. The driver

stopped, I got out, scooped Bingo up in my arms and jumped back on

the truck. The poor thing was absolutely terrified and was shaking

uncontrollably. For the rest of his life, whenever there was a

thunder storm, Bingo would hide under a bed until the storm

subsided."

"My sister and I eventually made our way home in

Halifax, only to find our parents had gone to Dartmouth looking for

us. When told the entire area had been evacuated, and no one was

allowed to enter, causing my parents a few anxious moments, but when

they returned to the house, they were overjoyed to

find us there safe and sound, and by and large unharmed. By then,

the authorities were encouraging all residents to evacuate the city,

since no one knew how far the fire would spread. They did know that

certain of the ammunition bunkers were in immediate danger and could

cause an explosion which would dwarf that which occurred earlier in

the evening. My father decided to accept the advice and we headed

for Herring Cove."

Stationed at Sandwich Point, Wedgepoint native Israel Pothier was

used to dealing with explosives. In the summer of I945, Captain

Pothier recalls hearing a "large crack" that people thought were

depth charges going over in the harbour. When word came in, he and

other military personnel found themselves conducting an evacuation

of Dartmouth.

“We were moving everyone down towards Eastern

Passage. The only ones who would not leave were a group of women

from St. John’s Ambulance who said they had to stay in case they

were needed," said Captain Pothier.

"We had just about everyone evacuated when the second blast came. I

was standing downtown, near the ferry terminal, when I saw a flash

towards the Bedford Magazine. I got down flat in the middle of the

street and when the blast came, the stores shook and the trees

almost bent down to the streets."

Traffic and communications were severely

disrupted by the explosions. After arrival of the Maritime Express

at 7:30 pm, all incoming trains were held at Windsor Junction and

there; was no information when they would be permitted to proceed

toward the City. Outgoing trains likewise were cancelled and the DAR

(Dominion Atlantic Railway) train scheduled to leave for the Valley

at 8:30 pm was kept at the depot.

Traffic on the Bedford Road was banned to all except official

vehicles. The usually well-travelled highway was dark excepting for

the occasional stabbing of the blackness by the headlights of

speeding ambulances conveyed by motorcycle escorts. The still of the

night along this picturesque highway was punctuated only by the

continuing explosions and the wail of sirens.

North End train service was discontinued early in the evening,

although Belt Line and Armdale cars were kept in operation until the

usual hour. Taxi pool switchboards reported a deluge of calls from

persons desiring to leave the City. They reported that the 20 cars

operating had succeeded in handling every

emergency call originating north of North Street, the area ordered

cleared by authorities. The pool reported that more than 200 calls

had been serviced, the cars filled to capacity, transporting more

than a thousand persons to destinations

along the St. Margaret’s Bay Road.

While telegraph and telephone companies reported no line

disturbances, they were unable to handle the rush of business. Long

distance telephone officials reported the deluge of calls from

people wanting to advise friends and relatives of their safety

exceeded the rush of V-E Day.

On orders from authorities, the Canadian National

Telegraph Company evacuated all employees from its operating

positions in the upper floors of the building at George and

Barrington Streets. The operators took up positions on lower floors.

Little food reached the weary evacuees who were moved out of Halifax

and Dartmouth along country roads the night of the great explosions.

They scrambled for food at cross-roads stores and stripped

farmhouses and cottages of what they

contained. Some of the evacuees were not only weary but hungry as

well, as they made their way back to their homes Thursday afternoon.

In the long procession every sort of vehicle had been seen,

including horsemen and horsewomen with blanket rolls and other

supplies tied about them. This was one of the strange features when

the sky was lit up by the fitful flashes from the Magazine; a dozen

or so horses trying to make their way through the jumble of traffic

headed for St. Margaret’s Bay.

Without fuss or excitement, the Control Centre had been speedily

manned by key personnel and the work began to run with rapid,

smooth, coordination. Consultation with Naval authorities on the

danger of further explosions enabled the organization to decide on

the areas to be evacuated. Citizens were directed out of the danger

areas, traffic diverted, and evacuation supervised. Temporary air

raid shelters were arranged for those who could not be moved. The

Control

center kept messengers and firewatchers posted, and citizens

responded "splendidly."

Emergency Services

The Red Cross had been given permission by

military authorities to use the Armouries as shelter for Halifax

citizens. It provided blankets, as did the Civilian Defence

Committee, and arranged for the distribution of food for groups of

citizens in various parts of the City.

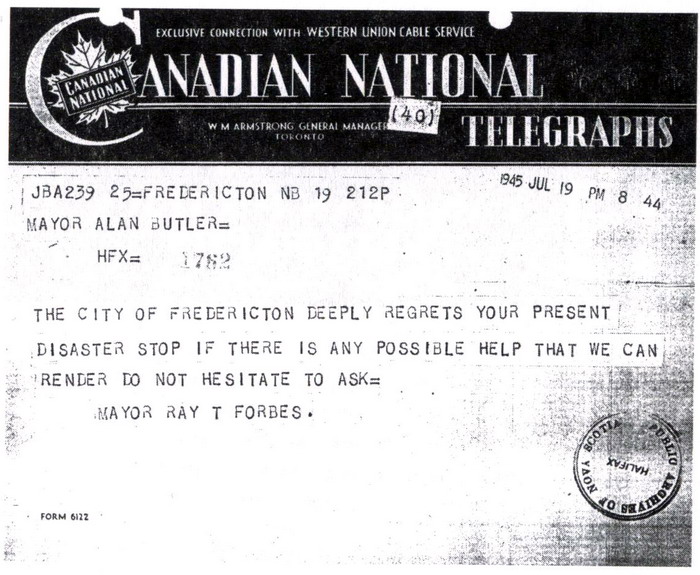

At the time of the explosions Mayor Alan Butler was out of town, so

the civic end of the business was being handled by Deputy Mayor

Sham. When the question arose of sandwiches and coffee for the

people on the Commons, Sham ruled: "Go ahead and dish them out. We

can let the council and the government worry about who’s going to

pay for them."

Between 1,500 and 2,000 residents of North Dartmouth and the Tufts

Cove area had been given shelter at A-23 Artillery Training Center

and the RCA (Royal Canadian Army) Base at Eastern Passage. Dartmouth

residents were also sheltered at the Somme Hall and Greenville High

School, and Clarence Park Recreational Hall in Eastern Passage.

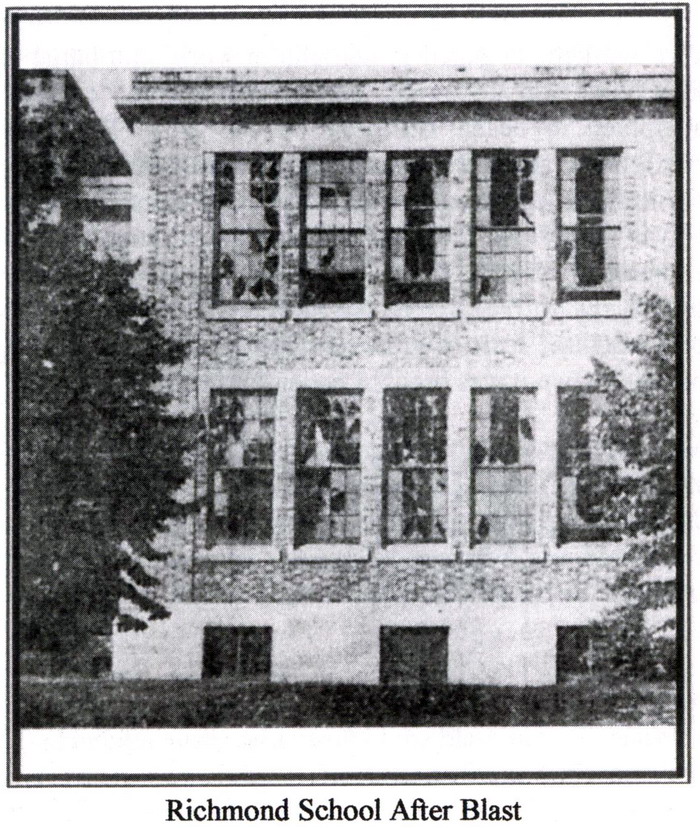

ARP and First Aid workers were called out immediately after the

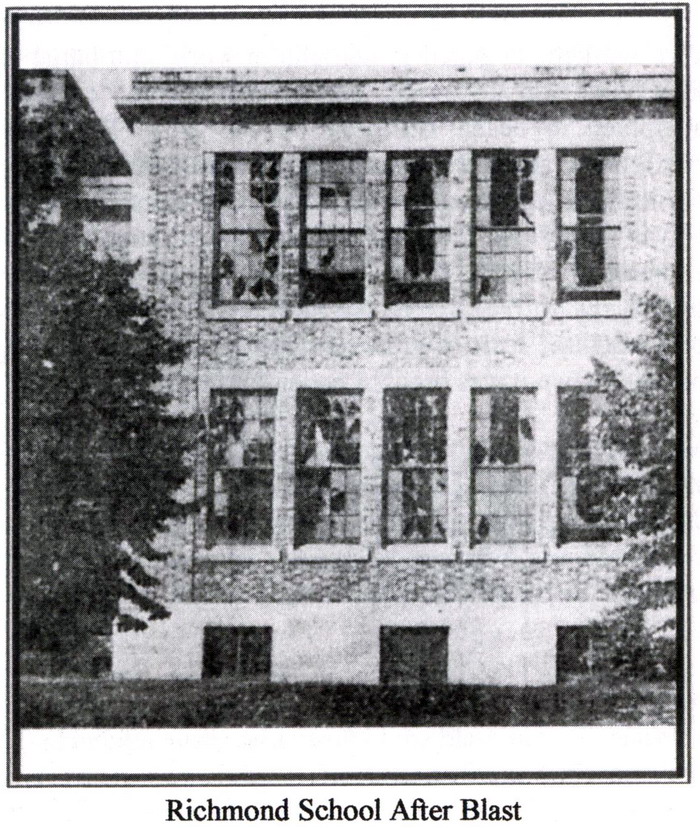

first blast. The Brandram-Henderson plant, Richmond School and

Alexander MacKay School were used as clearing points. After the

order for people to evacuate the North End, a first aid post and

blanket depot were established in the Armouries. There 3,700

blankets were distributed, while 200 were sent to persons who had

sought refuge at the Dingle and 500 to Francklyn and Point Pleasant

Parks.

Stretcher bearers and women members of the St. John’s Ambulance

Brigade were among those who remained on duty for 20 hours. The Red

Cross opened soup kitchens and used mobile canteens to feed

thousands. Ambulances were kept in readiness and workers helped

locate lost children and quiet any signs of panic among the fearful

crowds. When the evacuation to the south end began, First Aid posts

were moved to Point Pleasant Park and Gorsebrook.

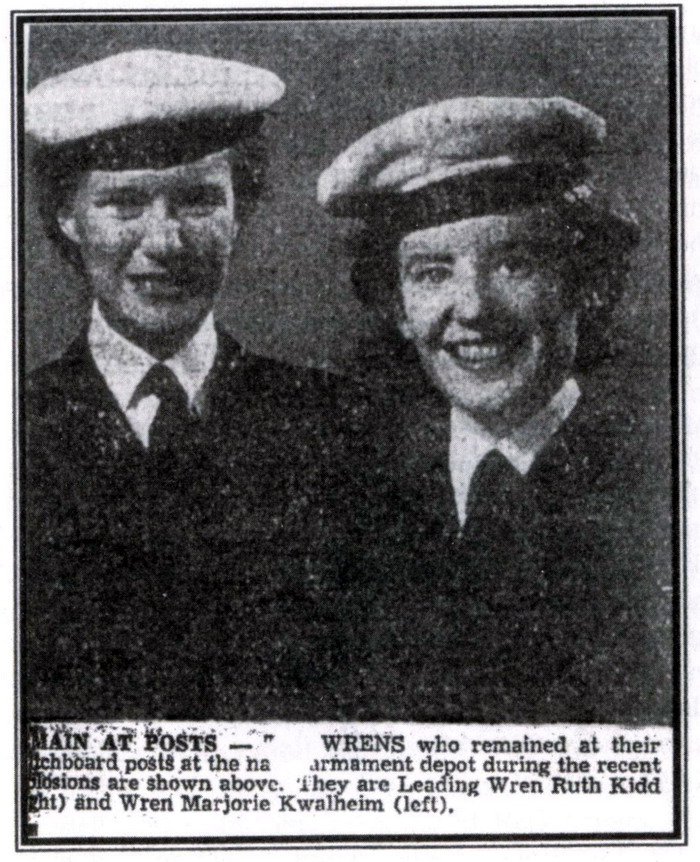

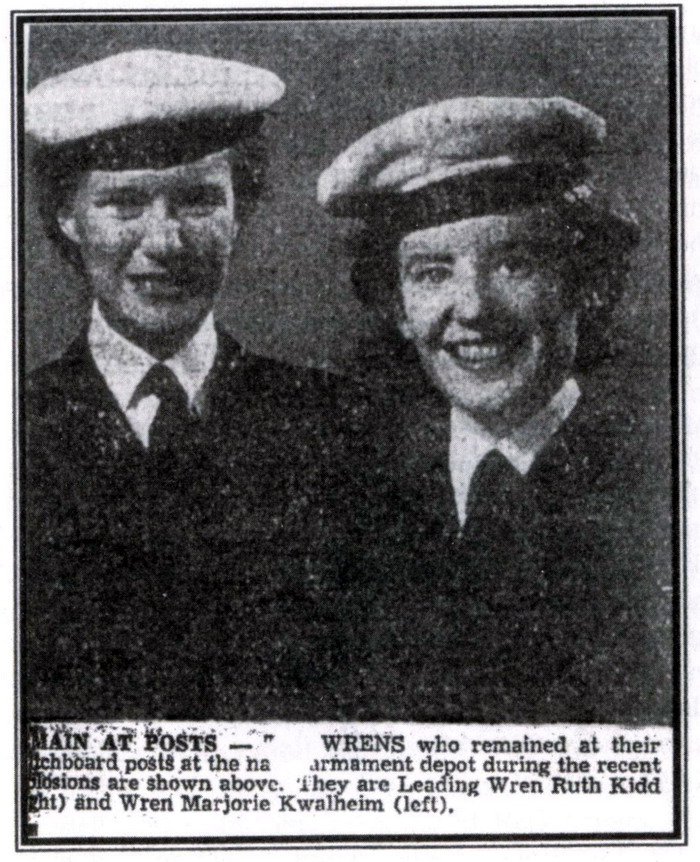

Lorna Innes wrote about the explosion in the Halifax Nova Scotia,

Saturday, July 13, 1985: "At the Naval Armament Depot, three miles

from the Magazine, Leading WREN Ruth Kidd, and WREN Marjorie

Kwalheim manned their switchboards in turns throughout the night.

They wore in helmets, ‘awkward things to work with when you have

headphones on.’ After the heaviest explosion at about 4:00am had put

the lights out, the girls worked by flashlight, putting calls

through from crouched positions on the floor. Plaster covered the

switchboard like snow. At the Dockyard, another WREN manned a

switchboard while shattered window glass fell around her."

Families provided with accommodation at the RCAF A23. Artillery

Training Centre, including the Military Hospital, and the Halifax

County Hospital, following their evacuation, speak highly of the

treatment received.

Everything possible was done for their care and comfort, declared

all who were interviewed after their return to their homes. "We

could not have received better attention, care and treatment, if we

had been paid guests," they said. "The personnel of the staff at all

these places were most kind and generous to us." Mothers with

infants and older children expressed themselves as most grateful for

the attention given and the generous meals served at regular hours.

The infirm, sick, and those suffering from shock were all placed in

the Military Hospital at A23, Eastern Passage, by special

arrangements made by Colonel Meighen. The Colonel came to Dartmouth

and supervised the transfer of large

numbers to the hospital, refusing not a single case even when he

knew the facilities would be overcrowded. Every inch of hospital

space was pressed into service. Many of the guests required special

care and attention. One confinement case was handled. As the

hospital was not specifically equipped to care for such large

numbers of nursing cases, an emergency call for feeding bottles and

nipples at 2:00 am on Thursday morning July 19, brought a ready

response from the Dartmouth druggists. One guest, speaking on behalf

of a large group said: "We cannot express in words the kindness

extended to us, the care and attention we received, and we are most

grateful."

More than 2,000 people, mostly women and children, were given food

and shelter in the Navy League establishments in the City of Halifax

throughout the night of July 18. The following day more than 15,000

meals were served to those

who were unable to find accommodation inside. Volunteer workers

laboured throughout the night to provide hot coffee, sandwiches,

soothe and wash frightened children, and help prevent the spread of

panic which would have been disastrous in the crowded quarters.

At the Merchant Seaman’s Club one aged lady, accompanied by her 80

year old husband brought her own stool to sit on. After a glass of

hot milk she went to bed and slept peacefully all night. One woman

reached the club with six children, complaining bitterly that her

husband was in jail for six months and they wouldn’t let him out to

give her a hand. Around midnight several women on the street outside

went into hysterics and had to be brought in and calmed. Across the

street a premature baby was born.

The Halifax Mail, July 20, reported that the Letitia,

acclaimed to be the world’s most modern hospital ship, was being

readied for emergencies and that it had been turned over for use in

the explosion-stricken Halifax area. The ship had been berthed at

Pier 20, five miles from the scene of the blasts after arriving on

July 16 with more than 700 servicemen on board returning from

Europe.

Services of the mercy ship’s staff and the facilities of her medical

equipment were offered soon after the first detonations rocked the

harbour. Fifty-eight patients were transferred by ambulance from the

Halifax Military Hospital to the Letitia. Five were members

of the Veteran’s Guard of Canada, who were injured while on duty at

the Joint Services magazine when the original explosion occurred at

approximately 6:30 pm on Wednesday July 18. None of their conditions

was considered to be serious. The other 53 patients recently

returned from fighting in Europe. No returned veterans remained in

the hospital. Reasons for the move were to allow greater room in the

hospital for handling explosion casualties. The hospital itself was

believed not be in any danger.

Emergency services were made quickly available to the thousands

affected by the Bedford Magazine explosions. It is apparent that

although the war was over, facilities and organizations were

fortunately still in a state of preparedness.

Chapter 3, July

19 Explosions Continue

Huge quantities of ammunition were embarked in ships alongside docks

in Halifax, because it was the only Canadian high explosives export

centre and the single depot for stocks going to Britain during the

war, and later to the Continent.

Thousands of Halifax citizens were aware of this. They did not know

from night to night, how soon or how late a great catastrophe might

occur. The danger was continuous and there was no averting it, but

the City, as a national port, took

this in stride. There was no complaining nor any demand that the

movements of explosives be handled at some other, isolated and less

congested port. lt was looked upon as part of the war effort, and

that Halifax, as a naval and export base, must make its

contribution.

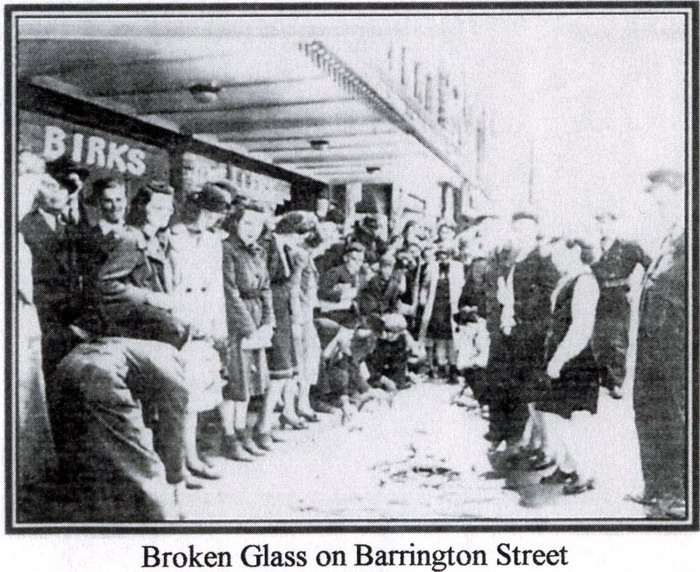

At about 3:30 am on July 19 there was a major explosion which

knocked out nearly all the plate glass on Barrington Street. Those

who saw it said that the preliminary flash lit up the whole

countryside as bright as day. The big Acadia Sugar plant in

Dartmouth had been stuffed full of munitions during the greater part

of the war. It was the possibility this might "go up" that led to

the early evacuation of Dartmouth. This was unlikely because the

plant was about four miles from the Magazine. The only real chance

of an explosion there would be as a result of the Magazine fire from

a heavy concussion, or by being hit by a stray shell.

In The Warden of the North, Thomas Raddall wrote about the

events that frightened all of the citizens of the extended Halifax

area. "The worst explosions came in quick succession about 4:00 am

in the morning of the l9th, rocking buildings, shattering glass, and

tumbling plaster and crockery. The design of the Magazine prevented

the whole thing from going up at once, but there was a particular

store of high level explosives which could level the whole north end

of the city, and naval headquarters continued to warn the remaining

population of a terrific blast yet to come. Still the stoics

remained. The telephone, broadcasting, and power house staffs stayed

at their posts. Household radios, turned on full,

blared through the open windows of a succession of bulletins and

warnings mingled with strains of music. This was the strangest part

of a weird night for those still crouched or lying on the ground."

The explosion was heard 219 miles away in Yarmouth County. Those

calling claimed they heard the noise or experienced the accompanying

concussions of sound from the time of the first blast which shook

the Halifax area. Many within the town limits of Yarmouth itself

heard echoes of violent explosions from late evening, near midnight,

at four in the morning, and later around 6:30 am. The times

coincided with the actual blasts in every detail. It was also

Iearned in Halifax that cloud reflection caused by the fire and

explosions could be seen quite clearly on the highway between Truro

and New Glasgow, and even as far away as Antigonish.

Later in the afternoon on Thursday, July 19, the danger of new and

greater explosions at the Magazine had decreased materially, and

restrictions were relaxed. Rear Admiral G. C. Jones made the

announcement on his return from a personal inspection trip to the

flaming munitions storehouse. This was reported in the Halifax

Mail, which went on to relate that the Firefighters were

believed to have the fire under control. They had been assisted by

the City’s fireboat Rouille which was pumping water to the

buildings along the waterfront at the Magazine, where huge

stocks of high explosives had been letting loose for 18 hours with

only minor let-ups.

On his return from the inspection, Admiral Jones issued the

following statement: "Following an aerial survey of the Bedford

Magazine area early this morning, a rough examination has been made.

Naval fire and patrol parties are controlling the area. It is still

dangerous and must be avoided, except by those on official business.

Rail and bus traffic on the Halifax side has been resumed."

Said one observer, "Admiral Jones went right into it at the height

of the morning explosions. Of course he went down in the mud every

time we did; with the stuff that was flying around. He’s got guts

all right ..."

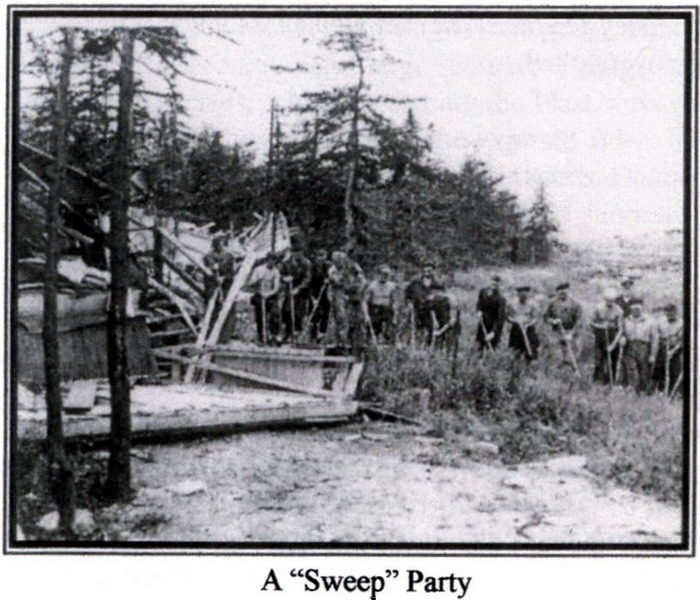

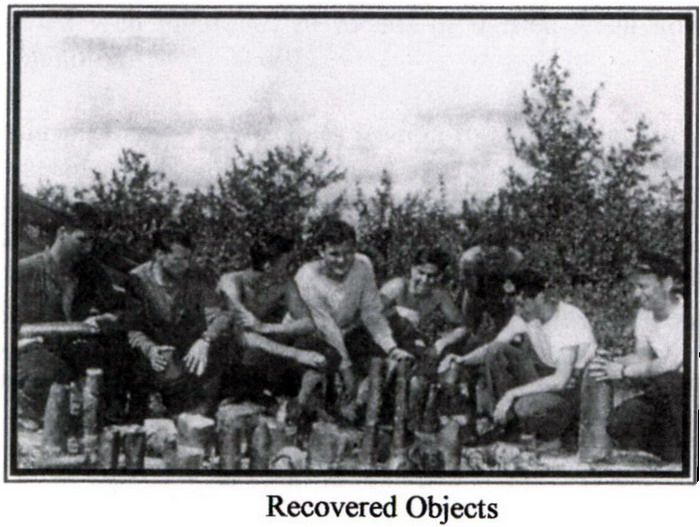

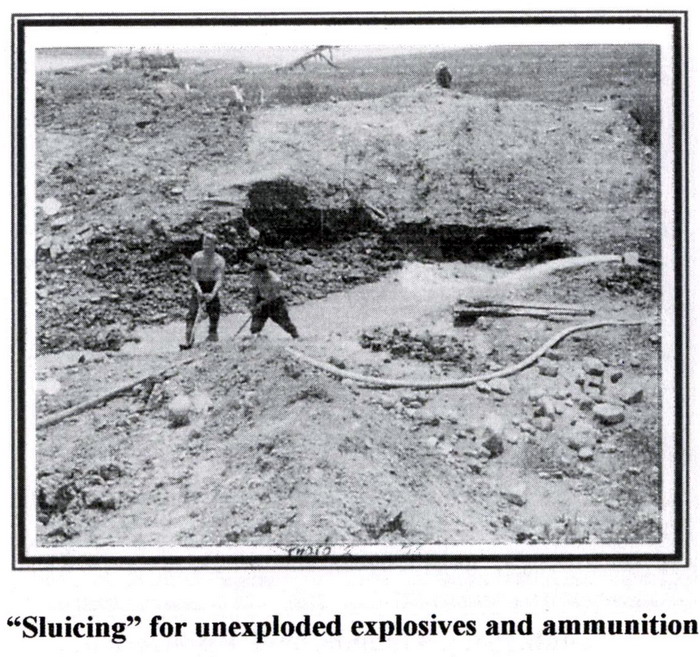

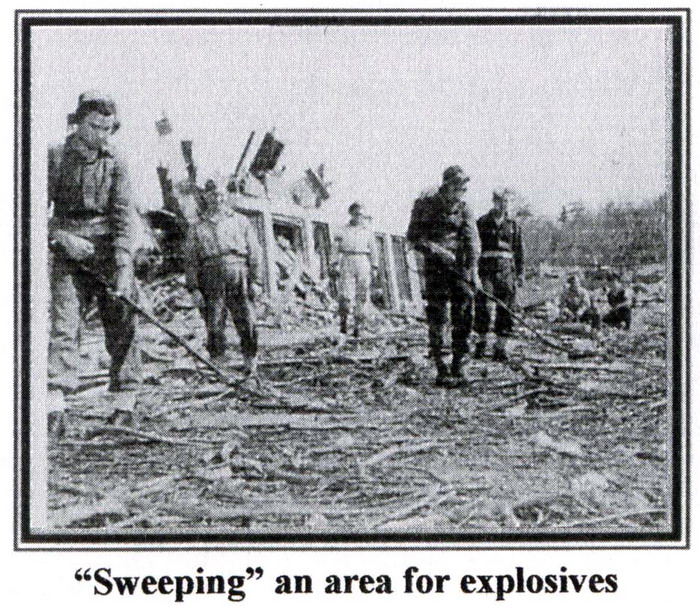

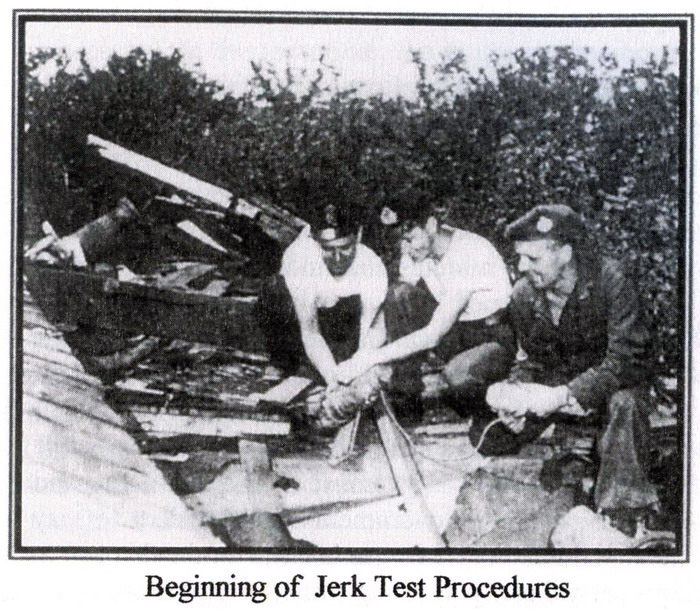

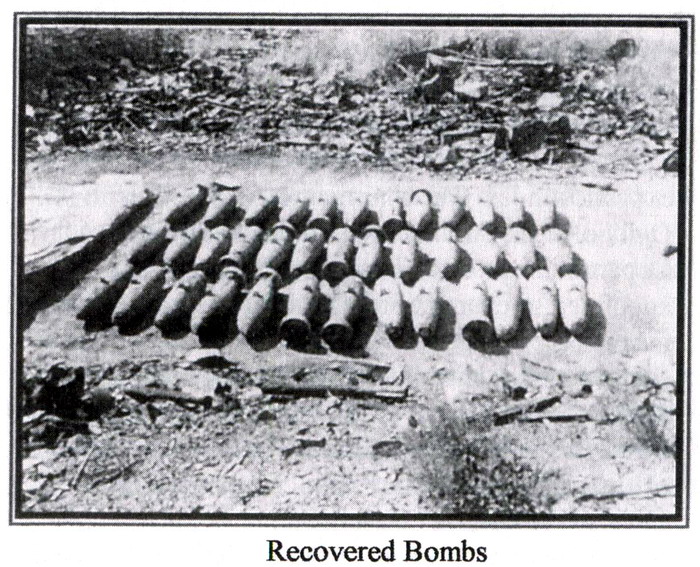

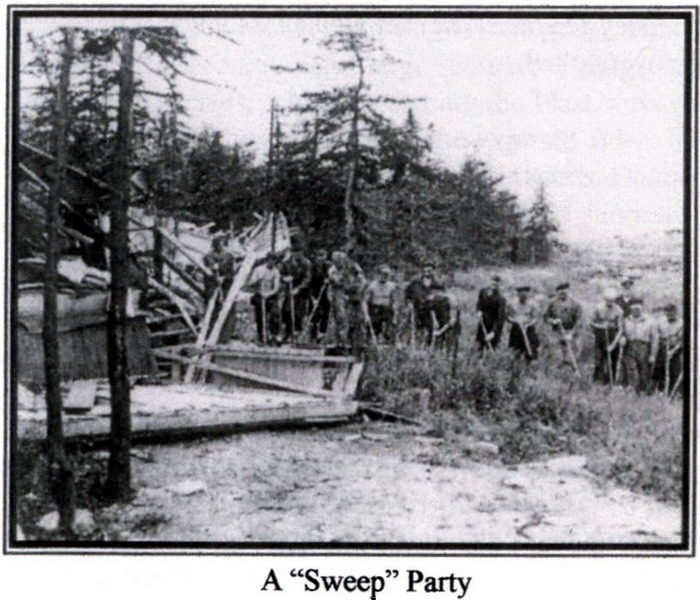

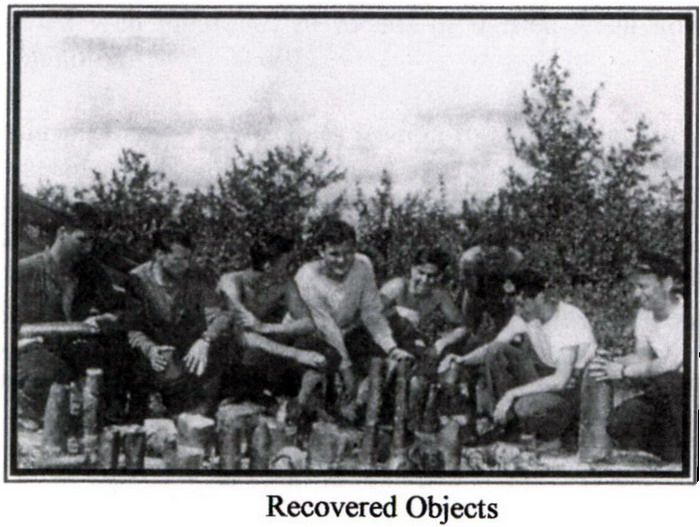

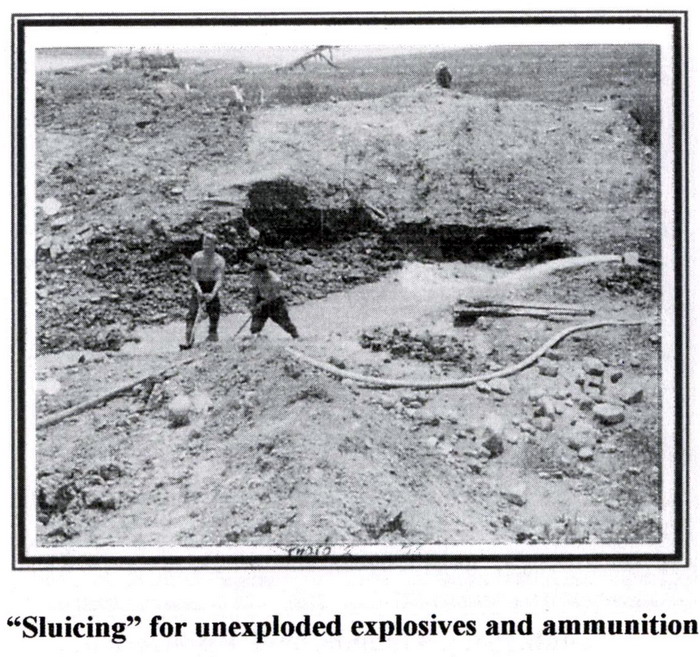

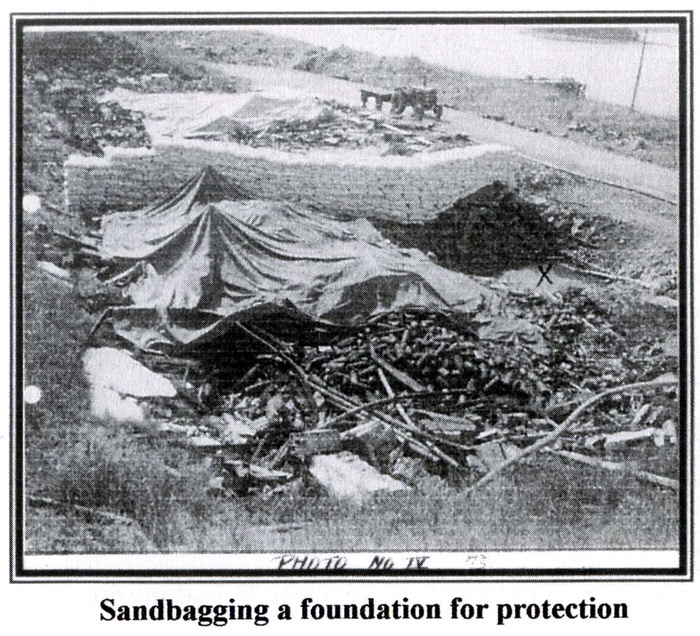

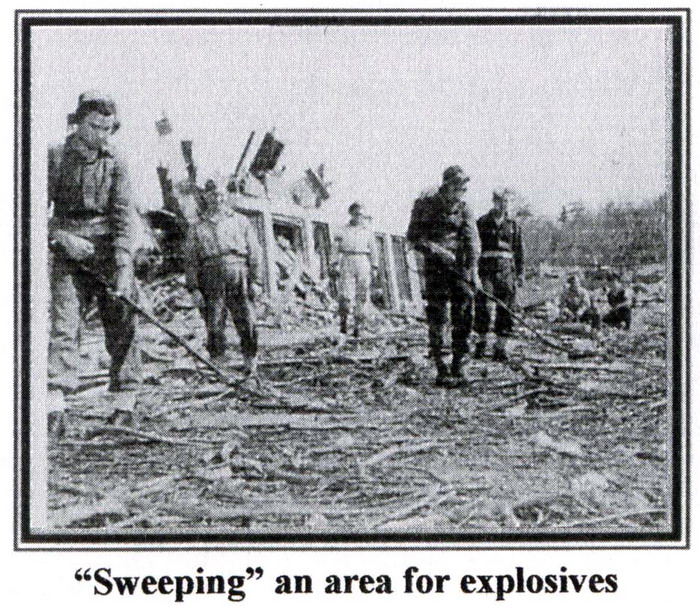

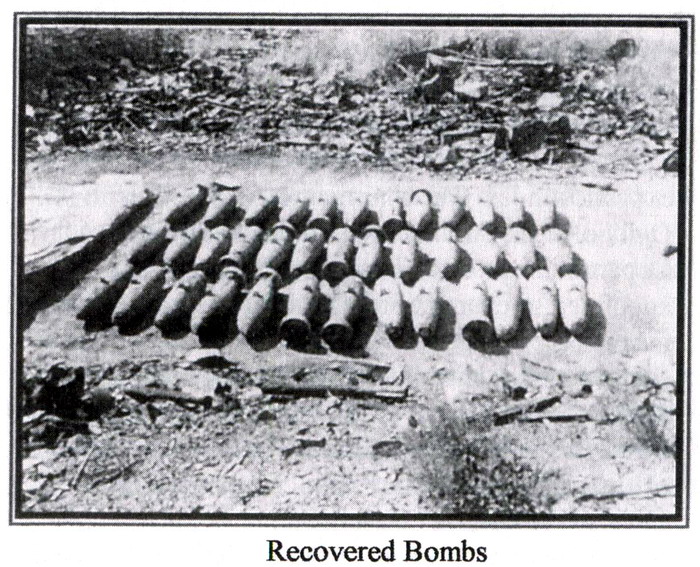

Compounding the problems, hundreds of tons of unexploded shells,

parachute flares, and ammunition for anti-aircraft guns were thrown

into the ground over a wide area. They were down from five to thirty

feet, and no one knew then how to

move them. Traffic in the area was halted until the roads were

hand-swept for explosives. The explosions had damaged water mains,

adding to the problems of the firefighters.

Although the Navy had cautioned that the fires were very difficult

to control, miraculously by sundown of the following day only minor

bush fires continued to burn. With risk of more explosions

pronounced "small and remote," people began to return to their

homes. But even with assurances from Mayor A.M. Butler, many

remained unconvinced and families camped for one more night.

Haligonians finally discovered that rumors of dead, dying, and

injured had been grossly exaggerated.

On Thursday morning, over 75% of the shops, stores and restaurants

located in the main business section of Barrington Street were

either closed or expecting to close before noon according to a

survey made earlier in the morning. Reasons

given for the closings were mostly lack of staff. Other reasons

however, were broken glass, staff needing rest, and because the

"other fellow" is closing. Practically no restaurants in the main

downtown district were open by 10:00 am, and it was difficult to get

a cup of coffee.

All naval and merchant ships containing explosives were removed from

the danger zone around Bedford Basin to places of safety at the

south part of the Harbour. Corvettes, destroyers, and other naval

craft occupied berths at the mouth

of North West Arm, and behind George’s Island. They remained there

until the danger of further explosions was over.

Most merchant shipping agents had reported they did not consider it

necessary to move ships which not containing explosives. The fire

ship James Battle was standing by at the Halifax Shipyards

along with the smaller Rouille. Cunard White Star reported

that the troop ship Ile de France had left port earlier in

the morning after being cleared the day before.

The stories told by Halifax residents are many. It was not only

those who were in the direct path of the explosion who suffered

injury. One man, eager to gain a better view of the blast, leaned

out of his fourth storey window just as another explosion occurred

and down came the window with the gentleman’s neck still under it. A

Halifax woman was discouraged from standing in open doorways, when

pausing in the front door of her home, another explosion slammed her

door shut, and propelled her down the hall. Another woman was

distraught at the loss of her heirloom china, while her neighbor’s

only casualty was a dozen eggs.

Efforts to revert to normal conditions were readily marked with

surprising results. Weary and fatigued workers pushed ahead to

re-establish home life which had been disturbed with dramatic

suddenness from the disaster. Lack of rest and food did not deter

them from carrying out their work of community service until long

after the regular hours of a working day. The morning and part of

the afternoon of July 19 marked the slack period in comparison to

what followed from the hours of 4 pm to l0 pm. lt was during these

hours that the heaviest part of the important and pressing demands

were handled with success and dispatch. lt was during this period

that things just had to be done. And they were done.

Reports of families stranded overnight in the woods, while deadly

blasts rocked the countryside were investigated first thing Thursday

morning. Investigation unfortunately proved them to be true. One

case involved the parents and their five children, ranging in age

from one to fifteen years. The eldest child of this family was a

girl of fifteen. They belonged to the Tuft’s Cove district. All

during Wednesday night and Thursday morning they feared every moment

they would be hurled to their deaths from the flying of metal or

suffer concussion from the blasts. The plight of the parents and

their family was pitiful and everything was done for them once they

were located. Walter Meridith heard of an ARP group in

North Dartmouth that was the first to discover the case and, with

assistance, had the family removed to comfortable quarters.

Three women and two men paralysed with fright, were found in the

cellar of what was left of their home, one and a half miles from the

centre of the danger zone. When the evacuation of all families in

the area was ordered late Wednesday, these distressed people just

could not muster sufficient courage to leave what they felt was

their only means of protection from the great danger which

surrounded them. So they remained hidden in the cellar of their

home, surrounded by trees and brush.

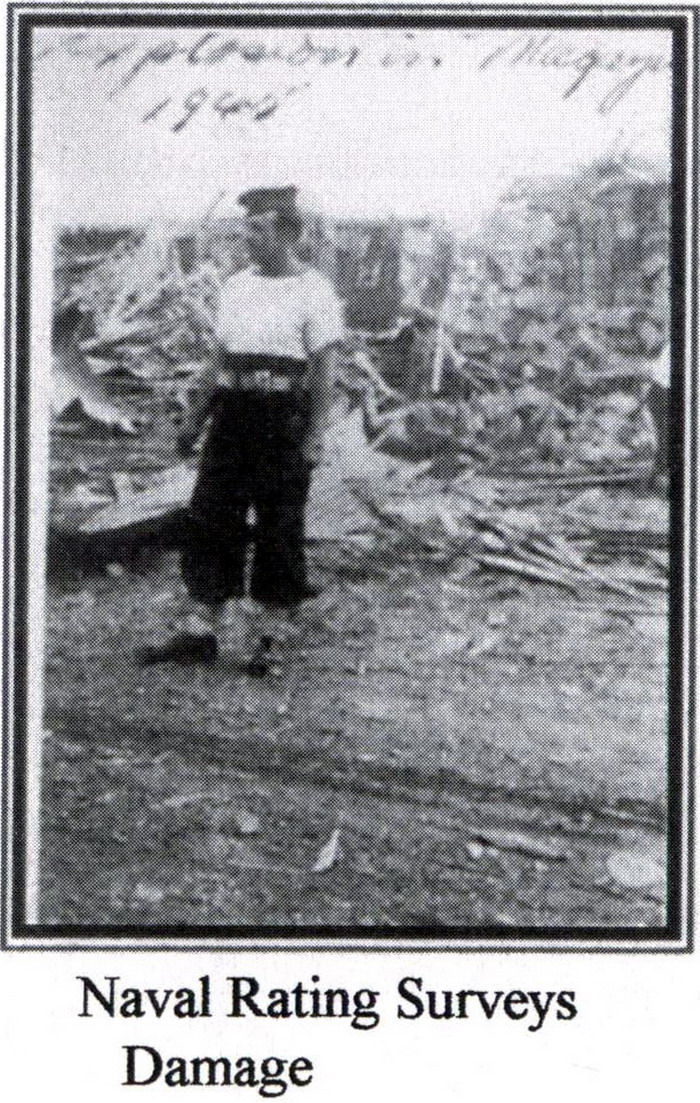

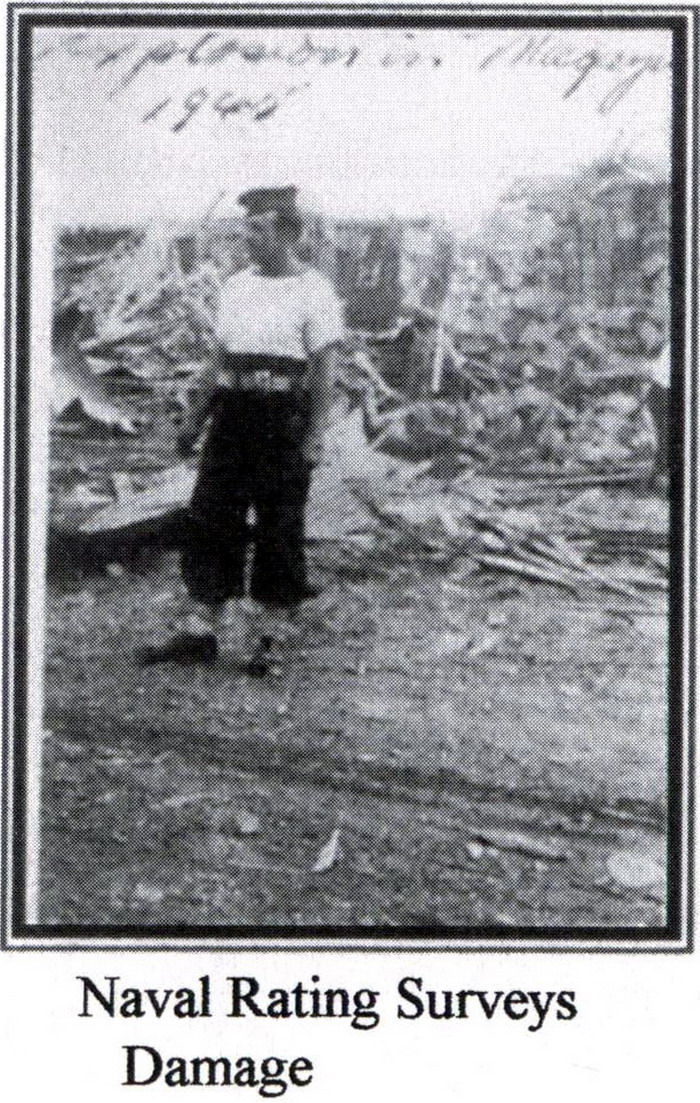

Excellent news pictures which showed some of the devastation in the

initial explosion at the magazine, were taken by the well-known

Dartmouth photographer, Allen Benjamin. As the explosions occurred,

Benjamin proceeded to the danger area and succeeded in getting

graphic pictures of the scenes of destruction.

Newspapers reported on several "human interest" episodes. A west-end

home, abandoned when windows started to fall in on the occupants,

was invaded by looters, who were foiled in their attempts by a l7

year-old boy brandishing a revolver. Unnoticed by the looters, the

barrel had been removed from the revolver.

Add one female deer to the known casualties of the explosion.

Fleeing in long-legged bounds from the flames and rumbling blasts,

which muttered angrily from the Bedford Basin yesterday, the doe

swam the harbour waters, and entered the Halifax Shipyards. Here it

suffered a broken back when it attempted to jump a ten-foot fence

near the railway tracks in the yards. Yard workers including Ben

Shaw, No. 1 Staff louse, saw the deer kicking in agony, and

mercifully ended

its suffering.

A Buffalo, New York woman, Mrs. Charles McKenzie, visiting Halifax,

and feared to be injured in the blast, had been blinded in the Great

Halifax Explosion of 1917. Her husband appealed to the rationing

board in his city for gas to drive to Halifax, but his request was

denied. She was visiting her father here, but his address could not

be confirmed, and police said they had not been contacted on the

matter. Local telegraph offices said it was possible she received

the telegram from her husband and attempted to reply, but due to the

thousands being sent out at that time, it was possible her reply was

delayed.

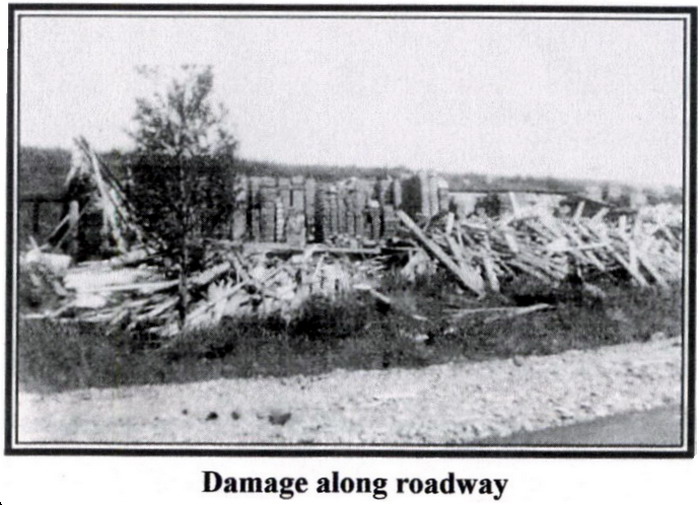

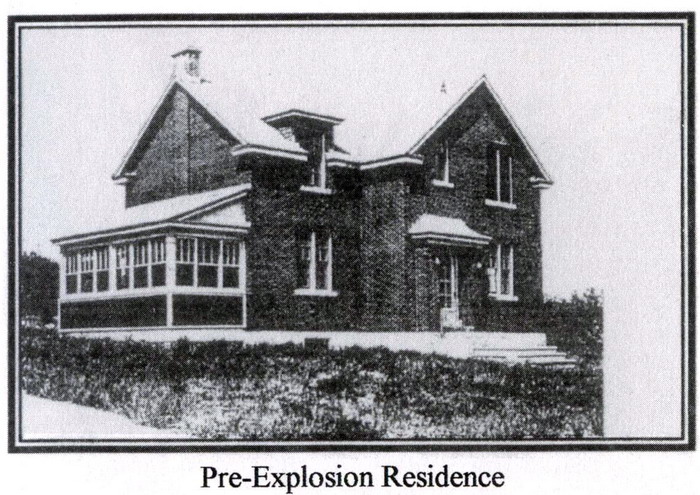

Peter Hayes, in the Daily News reported on the "Other

Explosion." The northern portion of Halifax presented a forlorn

sight the following day (July 19). Very few windows were left,

shingles were tom off roofs and houses, and things were generally in

a state of confusion. Some people returned to their homes to find

plaster hanging, wallpaper ripped from the ceilings, brickwork

shattered, and houses looking as though a cyclone had struck."

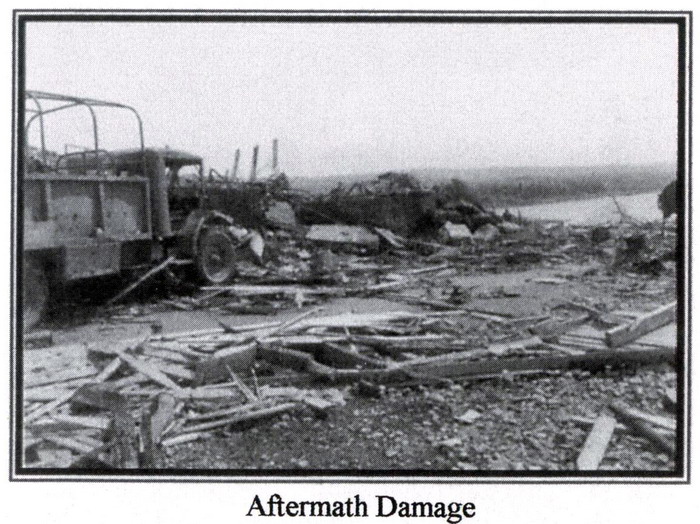

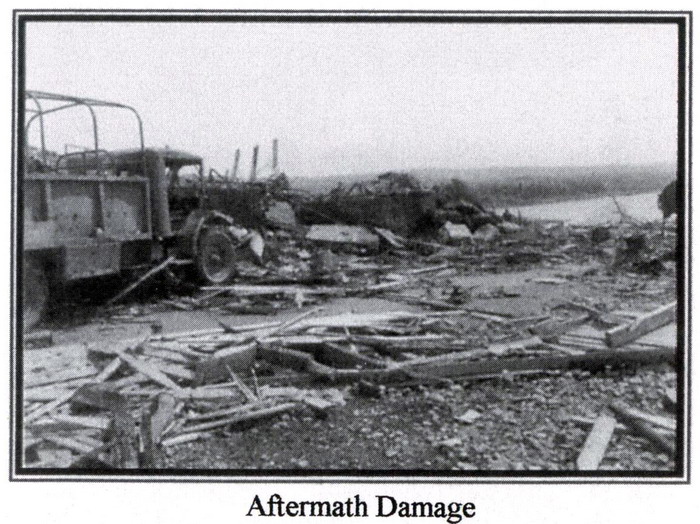

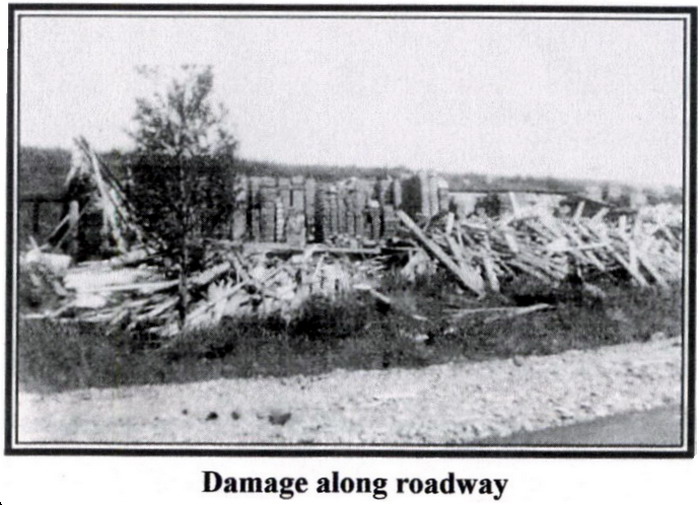

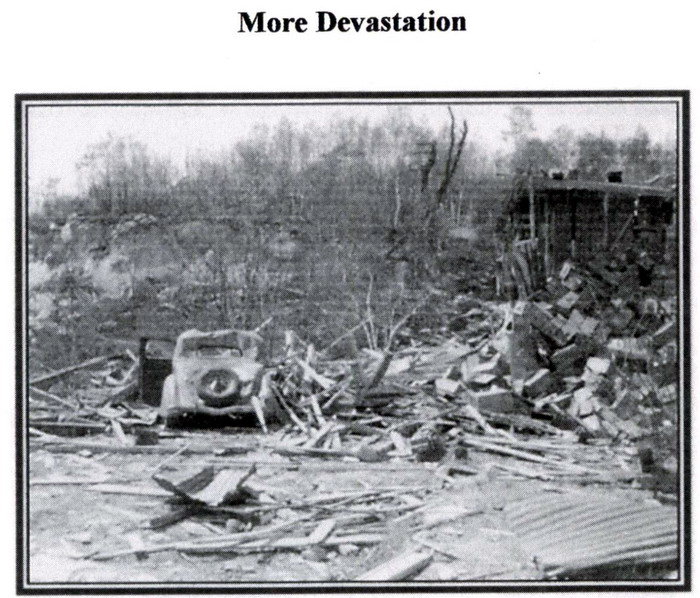

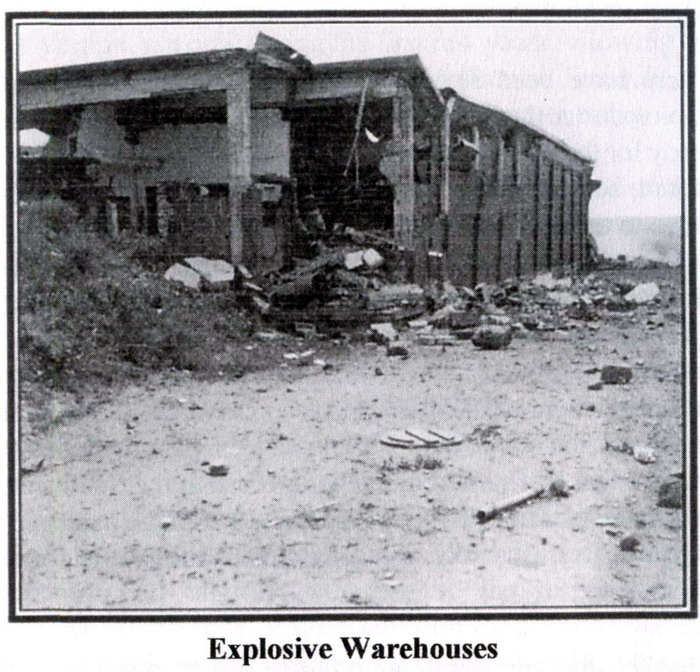

Buildings, wharves, and sheds had disappeared. There was nothing to

be seen but shreds of charred timbers, gaping craters, and bare

earth. It was the older section of the property which had suffered

the most damage. There the magazines had been separated by only

earthen walls, instead of the concrete blast blocks used in the

adjoining more modem erections. Two wooden piers and probably a

dozen small, scattered ammunition dumps, none more than one storey

high, had disappeared.

Until records were searched, it was impossible to

estimate the quantity of ammunition destroyed, or the value of the

wrecked property. The other two-thirds of the area, containing the

main magazines while suffering some blast damage, was chiefly

intact.

In spite of the devastation and confusion, some interesting events

continued without significant interruption, including a wedding at

St. Mathew’s United Church Thursday evening. During one of the heavy

explosions early on the morning of the l9th, a piece of glass from

the bell tower window severed a coupling pipe in the bellows, but

the couple, not to be outdone, went on with their wedding without

music. Flying Officer Robert Woolsey, was united in marriage with

WREN Helen Rose.

Among the heroes of the night were firefighters from the National

Harbours Board’s fire patrol. Chief James M. Coady, describing the

work of the crews of the two fireboats, James Battle and

Rouille said, "All on board proceeded to the scene at great

personal risk. I feel very proud to be privileged to command a crew

of men who showed so much devotion to duty and who went into that

inferno. I am thankful to Almighty God that they came out again

...... "

The Battle, commanded by Captain Howard Verge with fire crew

commanded by Captain John Zong, and the Rouille controlled by

the Halifax Fire Department and commanded by Captain George Scott,

braved falling shells to work as close to the Magazine as possible

and put out a number of fires raging along the beach area. The next

day, the Rouille cruised along the shore of Bedford Basin, pouring

water on fires and extinguishing them. When civilians were allowed

to return to their homes later in the day, the move was made

possible "because scores of men had run the gravest risks to make

the community safe."

Captain Robinson, with other naval officers and men, stayed on the

scene throughout the night, in and out of the Magazine zone, "trying

to get a picture of what was going on, hopping from jeep to ditch

when discretion demanded it." Captain Robertson spoke later of the

courage of firefighters: naval, civilian, and volunteers. Of one

group he observed, "They took pumps to the top of a hill. Down there

were a lot of four-inch shells; they were popping off and going into

the hill and over the heads of the firemen who were trying to save a

big magazine building loaded with explosives."

The firefighters were standing on top of what turned out to be a

pile of depth charges, 400-500 in all. None exploded. "Then," added

Captain Robertson, "when that building went, we decided to get out.

There was no point staying." They withdrew to a safer place known as

Father Martin’ s Hill. They had a chart of the magazine buildings

and their contents and used this to follow the progress of the fire.

Thirty-five of the Magazine’s buildings were destroyed. "Finally,"

said Capt. Robertson, “when a 14-inch shell landed alongside us, we

got away from there."

The explosions had damaged water mains, adding to the problems of

firefighters. William Sawler, civilian foreman of works, raced to

the Magazine from Sunnyside. "When the pumping station power went

off, he stuck to the job with a gasoline driven pump sending water

down through to the navy’s firefighters in the heart of the

conflagration. Duncan Lynch was with him and when fuel gave out, he

set out afoot for Sunnyside to get more. The authorities would not

let him return and no one could venture in to tell Sawler, who

worked until the pump stopped of its own accord. Then he came out,

not knowing that for hours the mains had been broken and the

500-gallon machines had been driven back long before. The

firefighters had to be ordered out before they would leave."

Chapter

4, July 20 Returning Home, Recollections

As Raddall wrote, behind the announcements that the danger had

largely passed, "There was an epic of heroism and endurance on the

part of the men who for twenty-four hours had been struggling to get

the Magazine fires under control. Chiefly the credit was due to

naval volunteers who dragged fire-fighting equipment to the very

edge of the inferno and remained there throwing themselves to earth

for the greater explosions and working tenaciously at the blaze in

the intervals, in a rain of stones, broken brick, unexploded shells,

and whizzing fragments. As if the dangers were not enough, the

parched woods and brush all about the Magazine caught fire and

burned for two days."

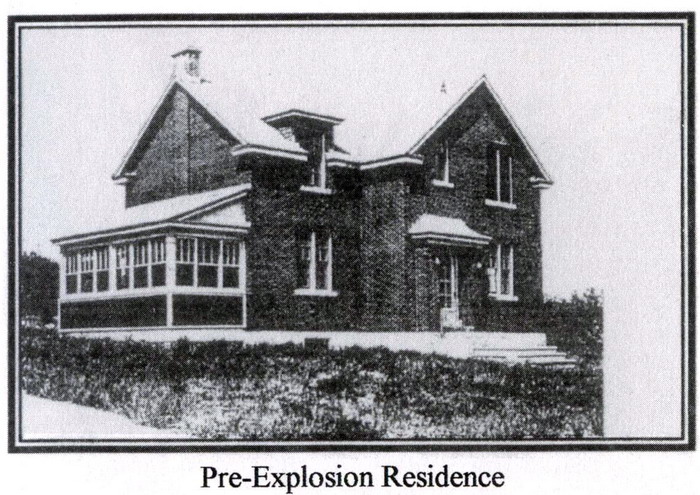

Interestingly enough the results of the explosions were mixed. In

the quarters of the Magazine staff, many window panes were left

intact, yet the heavy ironstone masonry of All Saints Cathedral in

the City’s south end, five miles away, was rocked and severely

cracked. A lighthouse keeper seventy miles away along the coast

reported a strange low rush of air about 4:00 am on the 19th, "as if

a cat had brushed against my legs."

At 6:30 pm on Thursday, July 19, on the advice of Naval Authorities,

Mayor Butler said that all might return with safety to their own

quarters. That finished the exodus, though many lingered through the

evening, finishing up what had

been to the children a great picnic day.

Not so for many of the elders. There was actual suffering. Added to

their anxiety over what was to happen if the reputed 50,000 depth

charges in the main Magazine went up, was the fatigue of the long

treks on foot through the City and along country roads. They spent

the night without sleep and the day was hot and humid. But the good

humour of the crowd on both sides of the Harbour continued, and there

was general appreciation of the work of the volunteers in manning

food

dispensing stations where thousands upon thousands of sandwiches and

cups of coffee were served.

The Mayor felt that there was always an element of danger in the

handling of explosives and this would continue. Amplifying this, a

naval authority said that one further explosion of a minor nature

was possible, but only remotely

possible.

As the body of Henry R. Craig, patrolman, the lone casualty was

brought to the City from the Magazine, life went back to normal in

Halifax. Offices opened, factories resumed operations, services were

restored, and thousands of families picked up where they left off at

6:35 pm in the evening of July 18, many of them well fed for the

first time in a 24 hour period.

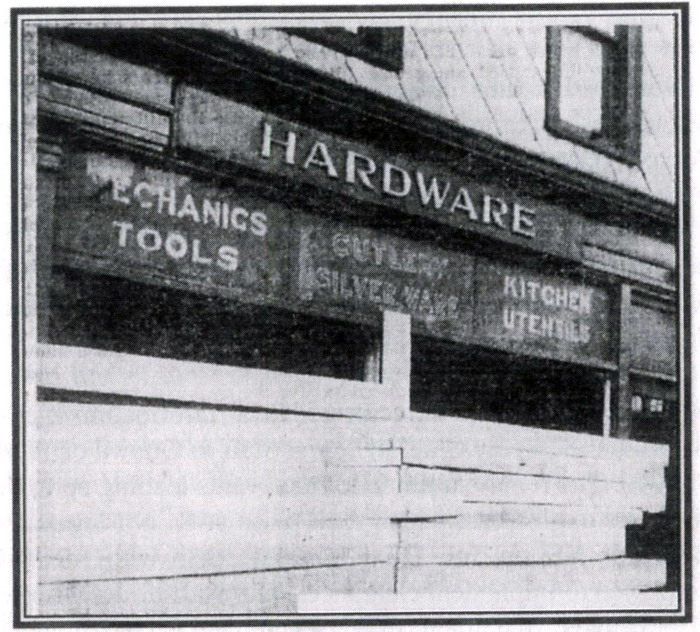

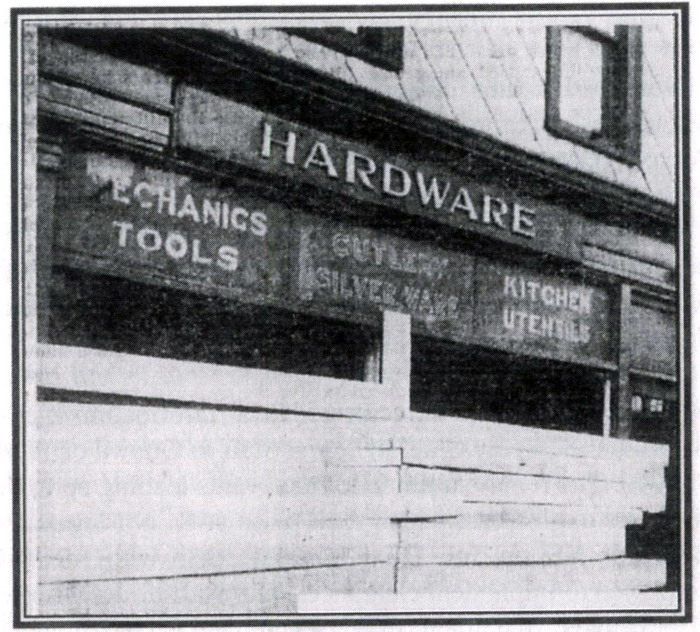

Business blocks were boarded up. Cleaners had carted away the bulk

of the broken glass which had strewn the pavements in Halifax and

Dartmouth. What the cost of the blast would amount to had not yet

been estimated, but so far as windows were concerned, more seemed to

have been knocked out than during the V-E Day riots.

The question of reparation was on the minds of citizens. The mayor

reported that on commercial establishments, payment would be depend

on whether or not insurance policies had been taken out by the

owners. Civic property was covered and would call for substantial

payments for schools, as well as churches, which seem to have been

the main sufferers.

One example of "making do" was at the City Market. There the windows

were badly smashed and countrymen and dealers were forced to vend

their wares in the open. Before 7:30 am on July 20, the crowds of

buyers had begun to assemble, grabbing what they could from

partially filled benches. However, grocery stores reopened, and

general food supplies were back to normal. Milk deliveries which had

been called off, were undertaken again, and dairies reported

adequate supplies. The same was true of the bakers.

About half the City went without mail, although because most

businesses were closed, and many people away from their homes, the

inconvenience was not significant. Post Office officials said that

only half the regular work force of letter

carriers showed up for work on Friday morning, July 20.

Although train traffic into and out of the City was suspended during

the series of shattering blasts, little congestion resulted. There

was not much freight moving at the time, and when the "all clear"

was given, traffic was moved with dispatch. The incoming train, the

Ocean Limited, which had been held at Elmsdale Wednesday night, was

finally given permission to enter the City.

Theatres which had advised their audiences to leave after the first

blast on Wednesday, the l8th, remained closed until Friday the 20th.

Major O. R. Crowell, Director of Civil Defence, paid tribute to

co-operation and calmness shown by Halifax citizens to the work of

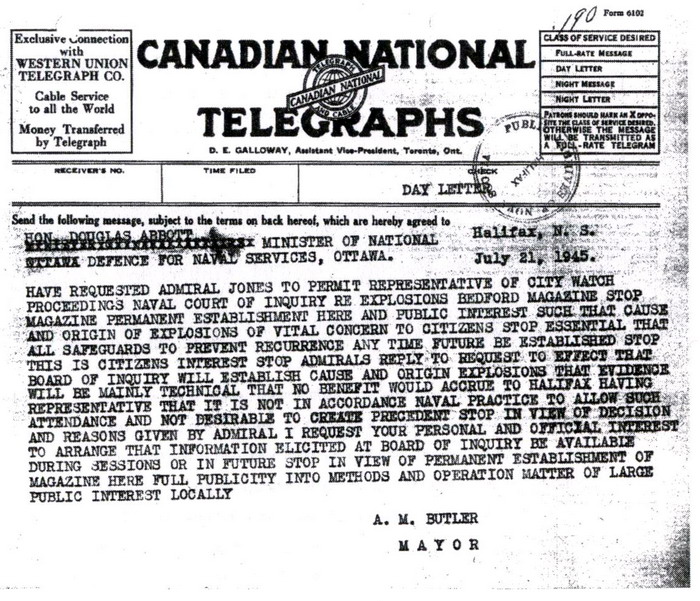

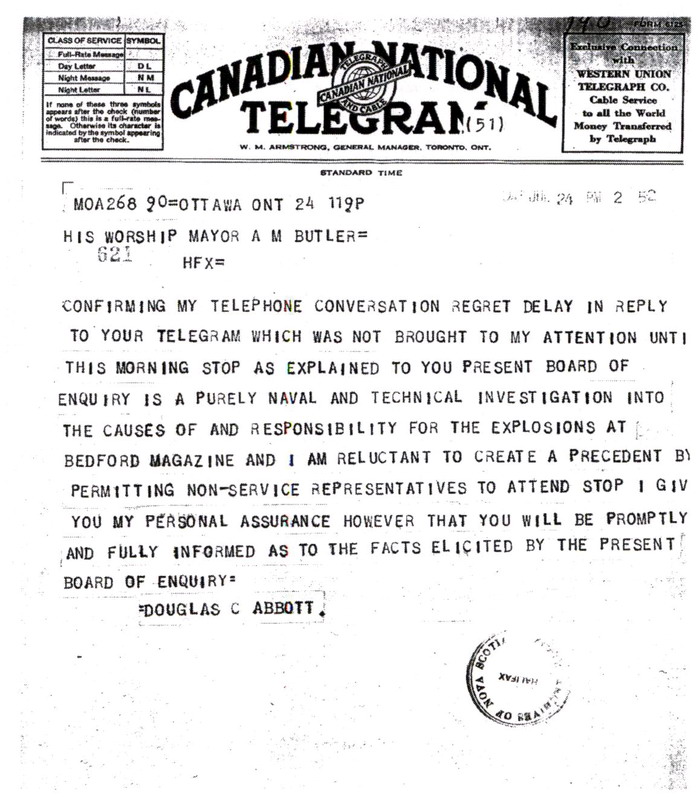

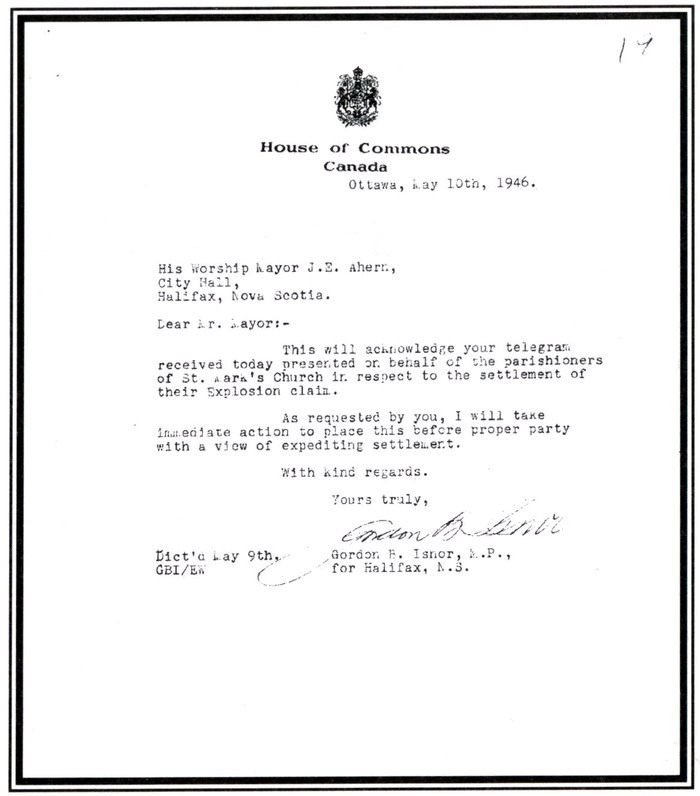

the Halifax Civil Emergency Corps, and members of the armed forces.